(12.) Maurice Nicoll 1 - SOME THOUGHTS ON THE WAR, Part II and THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN OBSERVATION AND SELF-OBSERVATION - pp.45-50

This is number (12.) of our sequential postings from Volume 1 of Maurice Nicoll’s Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky.

(If you are a subscriber to The Journal of Gurdjieff Studies, you can opt in or out of receiving emails from the Fragments Reading Club category.)

Links to each commentary will be put on the following Contents page, as we progress through the book:

45

SOME THOUGHTS ON THE WAR FROM THE STANDPOINT OF THE WORK - Part II.

Part II.—Everything based on violence can only create violence. There is not a single school of real teaching that teaches violence. Even the schools of Hatha-Yoga, such as the doubtful schools of Ju-Jitsu, do not actually teach violence but the method of overcoming violence, but this is often misunderstood and there is very much in Hatha-Yoga schools that is wrong and useless. Man—natural man—is based on violence and that is why he conducts certain planetary influences in the particular way that produces war. The planetary influences are one thing—neither good nor evil. It is man's inner state that translates them into good or evil. Man must overcome violence in himself. This is a very great issue, and a man must first of all study identifying in himself to its roots before he can understand what the overcoming of violence in himself means. War exists because man is based on violence. If he receives influences he does not know how to use and does not understand owing to his defective and undeveloped apparatus of reception, he cannot deal with them, and so they pass into irritation, anger or violence. Man is thus like a bad transmitter. He is evil because he transmits badly. If a man begins to deal with the small cycle of recurring events in his personal life more consciously and does not identify with some of them, he begins to be able to transform his life on a small scale. He transmits a little better and begins to be a little more free of the machinery of life—of the turning wheels surrounding him. If everyone did this, planetary influences acting on man would not so easily bring mankind to war. People could then resist war.

When war comes people find reasons for it and consent to it and feel almost as if they were willingly taking part in it. Whereas war, as a vast collective event, a vortex, has grasped them into its powerful influence and made them take part in it. But if necessity imposes itself on a man in this respect, even then he need not serve nature. He need not serve nature if he practises Karma Yoga—that is, if he does not identify with what he has to do and must do. But if he feel it is a fine thing to do what he is doing, he will identify and even go so far as to wish for rewards for his meritorious actions. To practise non-identifying can lead somewhere: to serve nature leads nowhere. There are no outer rewards for non-identifying. Everything a man does in regard to working on himself has no relation to the rewards of outer life. Only you know what you do in this respect. If called upon to do something as a good householder, a man must do what is expected of him as far as possible. But you must remember that the definition of a good householder is that he is a man who feels his responsibilities and acts accordingly, but does not believe in life. This, at first sight, is an extraordinary definition. Let us consider what it signifies from one side. A good householder, in the work sense, is a man who acts conscientiously, as when, for example, he holds office—not from himself, but from fear of

46

his reputation or for gain or in case he might lose power, etc. He does not believe in life, but sees life in a certain way and acts well, but not from himself. He does the right things perhaps but in a wrong way. This is why the path, or, as it is called, "The Way of Good Householder", is so long, and requires so many repetitions. You all know there is an important class of people who do their duty, not because they believe in life, but because they are influenced by merit, reward, ambition, power, money, and so on; and perhaps even by better ideals. They ascribe everything to themselves. Their attitude to life enables them often to act as if they were not identified. But they are identified in their own way. Yet they are very useful in life and give the impressions often of sincere action. And to themselves, they seem sincere and honest. But in any situation that demands real sacrifice of their position, etc., they hesitate and find various reasons why they should not act in this or that way. They are in life. But they do not believe in life. The Way of Good Householder is long because what is good in such people must be shifted from its basis and must become real and essential. A man may be a very good man mechanically, from personality, yet his goodness is not real. If a man does his duty in life as a good householder, he seems to come near to acting without identifying. Yet actually he is very far from acting without identifying. In the Gospels Christ attacked the good householder especially, when he attacked the Pharisees, and you must read for yourselves all that was said there about them and their meritoriousness. And perhaps Christ attacked them so powerfully just because they were the very people who could have understood and who would have been most useful. As you all know, this work attacks false personality, because it is unreal—that is, because it cannot form the starting-point of inner evolution. It would be possible to say very much more on this subject, but enough has been said to raise questions in your minds about the war and about understanding it from the ideas of the work.

Birdlip, July 24, 1941

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN OBSERVATION AND SELF-OBSERVATION

To observe and to observe oneself are two different things. Both need attention. But in observation, the attention is directed outward through the senses. In self-observation the attention is directed inwards, and there is no sense-organ for this. This is one reason why self-observation is more difficult than observation.

In modern science only the observable is taken as real. Whatever cannot be a matter of observation by the senses or by the senses aided

47

by telescopes, microscopes and other delicate optical, electrical and chemical instruments, is discarded. It has been sometimes stated that one of the general aims of this work is to unite the science of the West with the wisdom of the East. Now if we define the starting-point of western science on its practical side as the observable, how can we define the starting-point of the work? We can define the starting-point of the work as the self-observable. It begins, on the practical side, with self-observation.

These two starting-points lead in entirely different directions.

A man may spend his whole life in observing the phenomenal world —the stars, atoms, cells and so on. He may gain a great amount of this kind of knowledge—namely, knowledge of the external world—that is, of all that aspect of the universe that can be detected by the senses, aided or not. This is one kind of knowledge and by means of it changes can be made. The changes are in the external world. Outer, sense-experienced conditions may be improved. All sorts of facilities and conveniences and easier methods may be invented. All this knowledge, if it were used in the right way, could only be for the benefit of mankind by changing his external environment to his advantage. But this kind of knowledge of the external can only change the external. It cannot change a man in himself.

The kind of knowledge that can change a man internally cannot be gained merely by means of observation. It does not lie in this direction— that is, in the direction of the outwardly turned senses. There is another kind of knowledge possible to man and this knowledge begins by self-observation. This kind of knowledge is not gained through the senses, for, as was said, we do not possess any organ of sense that can be turned inwards and by means of which we can observe ourselves as easily as we observe a table or a house.

While the first kind of knowledge can change the external conditions of life for a man, the second kind of knowledge can change the man himself. Observation is a means of world-change, so to speak; self-observation is a means of self-change.

But although this is so, in order to learn anything, we have to start from knowledge itself and knowledge of whatever kind begins from the senses. The knowledge of this system of teaching begins with hearing it—that is, it begins through the senses. A man must be told to observe himself and in which direction he must observe himself and the reasons why he should observe himself, etc. And whatever he hears or reads in this connection first of all must enter through his senses. From this point of view the kind of knowledge of which the work speaks begins from the plane of the observable, just as does the teaching of any science A man must begin by giving external attention to the work. He must observe what is said, what he can read of it and so on. In other words, the work touches the plane of the senses. For this reason it can very easily become mixed up with the kind of knowledge that can only come through the study of what the senses shew, and as it were lie alongside

48

it or become stifled by it. And unless a man has the power of distinguishing the nature or quality of the knowledge taught by this work and the knowledge taught by science—that is, unless he has magnetic centre in him, which can differentiate the qualities of knowledge—this mixing up of two planes or orders of knowledge will produce a confusion in him. And this confusion will remain even though a person continues in the work, unless some effort is made to let the work pass on to where it belongs in himself. That is, he will judge of the work only by what he sees, by other people outside him and so on. The work will remain, so to speak, on the level of the senses. What then is the nature of the effort a person must make in this connection? He must effect a separation in his mind between two orders of reality that meet in him. Man stands between two worlds—an external visible world, that enters the senses and is shared by everyone: and an internal world that none of his senses meets, which is shared by no one—that is, the approach to it is uniquely individual, for although all the people in the world can observe you, only you can observe yourself. This internal world is the second reality, and is invisible.

If you doubt that this second reality exists ask yourself the question: are my thoughts, feelings, sensations, my fears, hopes, disappointments, my joys, my desires, my sorrows, real to me? If, of course, you say that they are not real, and that only the table and the house that you can see with your outer eyes are real, then self-observation will have no meaning to you. Let me ask you: in which world of reality do you live and have your being? In the world outside you, revealed by your senses, or in the world that no one sees, and only you can observe—this inner world? I think you will agree that it is in this inner world that you really live all the time, and feel and suffer.

Now both worlds are verifiable experimentally—the outer observable world and the inner self-observable world. You can prove things in the outer world and you can prove things in the inner world, in the one case by observation and in the second case by self-observation. In regard to the second case, all that this work teaches about what you must notice and perceive internally can be verified by self-observation. And the more you open up this inner world called "oneself" the more will you understand that you live in two worlds, in two realities, in two environments, outer and inner, and that just as you must learn about the outer world (that is observable) how to walk in it, how not to fall off precipices or wander into morasses, how not to associate with evil people, not to eat poison, and so on, by means of this work and its application, you begin to learn how to walk in this inner world, which is opened up by means of self-observation.

Let us take an example of these two different realities to which quite different forms of truth belong. Let us suppose a person is at a dinner-party. All that he sees, hears, tastes, smells and touches, belongs to the first reality; all that he thinks and feels, likes, dislikes, etc., belongs to the second reality. He attends two dinner-parties recorded differently, one outer, one inner. All our experiences are the same in this way.

49

There is the outer experience and our inner reaction to it. Which is most real? Which record, in short, forms our personal lives?—the outer or the inner reality? Is it true to say that it is the inner world? It is the inner world in which we rise and fall, and in which we continually sway to and fro and are tossed about, in which we are infested by swarms of negative thoughts and moods, in which we lose everything and spoil everything and in which we stagger about and fall, without understanding even that there is an inner world in which we are living all the time. This inner world we can only get to know by self-observation. Then, and only then, can we begin to grasp that all our lives we have been making an extraordinary mistake. All that we have taken as "oneself" really opens into a world. In this world we have first to learn how to see, and for this purpose light is necessary. It is by means of self-observation that this light is acquired.

ADDED NOTE

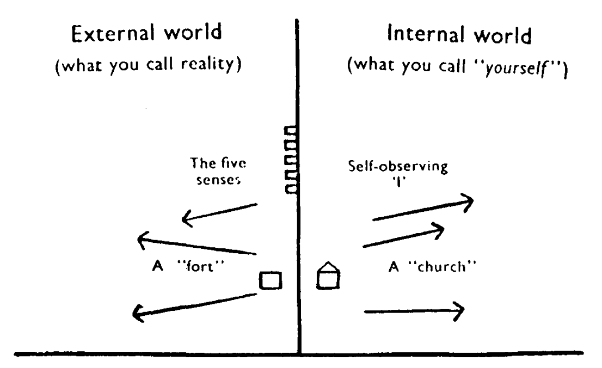

Let us represent the matter in the following diagram. Diagrams are useful because one can easily remember them and so they can act as means of recalling ideas.

As regards the internal world, what blocks our contact with it is all that this work teaches that we must struggle with—false personality and so on. All these wrong things in ourselves form, as it were, a thick cloud that prevents us from right contact with the influences reaching us from the internal world. When the work forms a definite point or "organism" in us, it begins to make a relation to the "internal world". This I call a "church" for the moment. It is comparable to what we have to form towards outer life—namely, what I call here a "fort". This is added owing to the conversation that ensued after the above paper was read at the meeting on Saturday last at Birdlip. The most

50

important thing to grasp is that we live in two different realities or worlds, one shewn by the senses, the other only revealed through work on oneself—through the purification of the emotions from false personality and the right ordering of the mind through the ideas of the work, so that relative thinking is made possible and a proper system of thought is built up.