(18.) Maurice Nicoll 1 - SOME NOTES ON WRONG WORK OF CENTRES, Part I - pp.68-71

This is number (18.) of our sequential postings from Volume 1 of Maurice Nicoll’s Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky.

(If you are a subscriber to The Journal of Gurdjieff Studies, you can opt in or out of receiving emails from the Fragments Reading Club category.)

Links to each commentary will be put on the following Contents page, as we progress through the book:

Birdlip, October 18, 1941

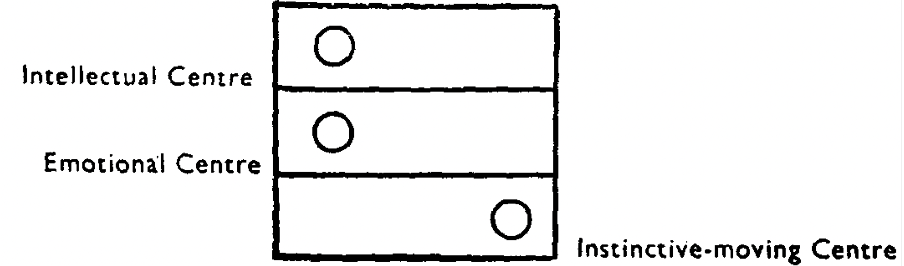

Part I.—One of the most interesting ideas found in this system of teaching is that man has several different minds and that the intellect is only one of the minds he possesses. Let us take the diagram of the different centres in man according to the teaching.

Each of these centres is "mind". Each of them represents a different kind of mind.

Centres can be roughly compared with very delicate and extremely complex machines, each machine being designed for a different purpose and use. Moreover, each machine is made of separate smaller machines or of machines within machines, and these can work by themselves. That is, the whole centre or whole machine can work, or only a small part of it. Everyone possesses these highly complex and delicate machines, but knowing nothing or next to nothing about them, people are liable to use them wrongly. In fact, they think they have only one mind and that this one mind can deal with everything. And the idea of one mind is linked up with the illusion that man is one—that is, with the form of imagination that everyone carries about with him—namely, that he is internally one, a unity, having one will and one permanent 'I', and possessing full consciousness and self-knowledge and the power to do. It is a very strange and interesting thing that no one can reflect upon deeply enough—for it leads to the source of man's inner "sickness"—that it takes so long before people can bear to realize that internally they are not one but many, that they are not a unity and harmony but a multiplicity and disharmony, that they have not one permanent and real 'I' but hundreds of different and quite contradictory 'I's that take charge of them at different moments, that they have no real will but a host of changing conflicting wills, belonging to each of these 'I's, that only rarely do they have moments of consciousness but usually are in a peculiar state of waking-sleep, and that as a result of all this they have no real power of doing and so live in a world where everything happens and no one can prevent it from happening. Even the idea that a man has not one mind but different centres or minds can be resented or regarded as being as fantastic as the saying that people are not conscious. No one in fact will face himself and his real situation.

So a man clings to what he imagines himself to be, and by clinging in this way to what does not exist, to what is unreal, makes it impossible

69

for himself to exist and to become real—that is, what he might become and actually is created to become. You perhaps have heard a saying in this Work that everyone can be a millionaire but in order to be a millionaire he must first realize that he is not a millionaire. In this respect everyone is like the rich young man in the parable, the man rich in feeling his own merit, who ascribed goodness to himself as his own possession and was deeply identified with his virtues. You remember that he was told to go and sell it all and give to the poor—that is, to the real or essential ungrown inner part of him, starved by the "rich personality". Now a man is not likely to take in anything that is said about the wrong work of centres unless he has reached the point of recognizing for himself that different centres really do exist in him. You must all understand that this is not a fantastic idea or a merely theoretical idea. It is a fact and it is a fact of the greatest importance to anyone who wishes to use his life well and not make it something blurred, unformed and largely meaningless. For this reason the first thing you are told to do in regard to practical work on yourselves is to observe which centre or centres are working at any particular moment. That is, you are told to practise self-observation, which is the only road leading to self-change, first of all in relation to noticing the different centres in you. But even this is very difficult and people do not, even after a long period, really see for themselves that these centres exist in them. Or they try to observe them for a moment and think that is all that is needed. There are three different people in everyone, to begin with—the Intellectual Man, the Emotional Man, and the Instinctive-Moving Man, corresponding to these three centres or minds. That is, a man thinks one thing, feels another, and "senses" a third—that is, his sensations, which belong to his Instinctive Centre, are different from his feelings, which belong to the Emotional Centre, and his thoughts, which belong to the Intellectual Centre. Let us suppose you are trying to keep an aim, and have taken the trouble to make this aim clear to yourself. Now suppose you get upset by something: what will happen, taking the matter only from the standpoint of different centres? If you are upset it means that the Emotional Centre has become negative. You feel angry, cross, disappointed, or perhaps you feel nothing is worth while. Now suppose you follow the mind of the Emotional Centre as it is at the moment will you be likely to keep your aim, whatever it is? No, of course not. But if you will get into your Intellectual Centre—if you can—and think about your aim and what made you make it and so on, then you may still keep your aim. Why? Because you are using the right centre for the occasion. You are not using the wrong centre, for to use, to follow, the Emotional Centre when it is negative is alwaysto use the wrong centre. But all this has been spoken of sufficiently before. To-day we have to speak of the wrong work of centres not so much in the sense of the wrong centres being used for any particular task, as for example, in trying to think how to run quickly downstairs, but in the sense of using the wrong part of a centre. As you know, each centre is divided into three parts and each of

70

these parts into three further parts. I am not now speaking of the division of some of the centres into positive and negative sides. Each centre reflects itself and the others in its three divisions and three sub-divisions. For example, the Intellectual Centre has three divisions, which represent the Instinct-Moving Centre, the Emotional Centre, and the Intellectual Centre itself, but all on a smaller scale. And these again are subdivided in the same way on a still smaller scale.

The Instinct-Moving part of any centre is the most mechanical part and it is in these mechanical divisions of centres that people spend their lives as a rule. But before we speak in detail about divisions of centres in general, one principle must be grasped relating to their divisions. Why do people spend their time in mechanical divisions of centres? The answer is simply that they require no attention. When attention is practically zero, one is in the lowest most automatic parts of centres. The result is that a person says and does things without any idea of what he is doing. Another result is that a person cannot adapt to any change or use his knowledge but behaves absolutely mechanically on all occasions and repeats what he knows like a machine. You all notice how hard it is for many people to adapt themselves to any new ideas or conditions, and how they repeat all they have been taught as if they were school-children.

To get into higher divisions of centres the effort of attention is necessary. This is the principle. Now let us take the mechanical part of Intellectual Centre as a starting-point. Its function is the work of registration of memories and impressions and associations and this is all it should do normally—that is, if rightly used. It should never reply to questions addressed to the whole centre. Above all it should never decide anything important. Now here we have the first example of wrong work of centres in regard to their parts and divisions. The mechanical division of Intellectual Centre, which is called the Formatory Part or Formatory Centre, is continually replying to questions and is continually making decisions. It replies anyhow, in slang terms, typical phrases and jargon of all sorts. It replies automatically and says just what it is most accustomed to say, like a machine. Or on a slightly higher scale, it replies always in a stereotyped way, like a schoolmaster or government official, using well-known sentences, party maxims, slogans, proverbs, wise saws, and so on. And the strange thing is that many people always reply in this way and never notice it, either because they cannot think about anything and rely on mechanical and even automatic expressions of the Intellectual Centre, or because they do not see the importance of thinking for themselves and freeing their thoughts from the mechanical words and expressions that belong to the lowest divisions of the centre.

We now come to attention. Attention puts us into better or more conscious parts of centres. Attention is of three kinds:

(1) zero-attention, which characterizes mechanical divisions of centres;

(2) attention that does not require effort, but is attracted and needs only the keeping out of irrelevant things;

71

(3) attention that must be directed by effort and will.

As was said, the first kind of attention, zero-attention, accompanies the work of mechanical divisions of centres; the second kind puts us into the emotional divisions of centres, and the third kind into the intellectual divisions. Let us take briefly the Intellectual Centre again as an example, as we shall have to return to this subject next time. The emotional part of the whole Intellectual Centre consists chiefly of the desire to know, the desire to understand, to seek knowledge, to discover, to increase one's understanding, to grasp and find out, to have the satisfaction of knowing, the desire for truth, the pleasure of learning, of reaching out; and, inversely, the pain of not knowing, the dissatisfaction of being ignorant, uninformed, and so on. The work of the emotional part requires full attention, but in this part of the centre attention does not require any effort. It is attracted and kept by the interest of the subject itself. The intellectual part of the whole Intellectual Centre includes a capacity for creation, construction, invention, finding methods, seeing connections, and bringing together apparently isolated things into an order or unity or formulation so that we see the truth of something hitherto obscure. This part cannot work without directed attention. The attention in this part is not attracted but must be controlled and kept by effort and will; we usually avoid doing the work belonging to this part of the centre, which is thus often unused.

Now from this we can notice in what parts of centres we are. Next time we will speak further on this subject.