This is number (20.) of our sequential postings from Volume 1 of Maurice Nicoll’s Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky.

(If you are a subscriber to The Journal of Gurdjieff Studies, you can opt in or out of receiving emails from the Fragments Reading Club category.)

Links to each commentary will be put on the following Contents page, as we progress through the book:

Birdlip, November 9, 1941

Part III.—The mechanical divisions of centres have their proper work to do and they can work rightly without attention, or with very little attention. When you walk, the action requires very little attention, and only from time to time, and all the complex movements involved in the act of walking are done rightly by the mechanical divisions of moving centre. You can prove that this is done by the mechanical division of moving centre because while walking your hands can be engaged in movements that require conscious direction—i.e. attention—as in sharpening a pencil or unravelling string, and so on. But just because the mechanical parts of centres can work with zero-attention or very little, occasional, attention, they often act independently—e.g. a man goes to dress for dinner

75

while thinking over a problem and eventually finds himself, to his surprise, getting into bed. Everyone must have noticed similar examples.

Now the whole human machine is made in such a way that one part can in an emergency do the work of another part for a certain time. This is expressed, in this system, by saying that centres overlap to some extent in regard to function. And although it is because centres overlap to a limited extent that the human machine can meet with certain emergencies and is therefore more capable of adjustment, it is actually because of the overlapping that occasions for the wrong working of centres are given. To take an example: we know that breathing can be carried on without our attention. Here the moving centre, which contracts and relaxes the muscles used in breathing, is controlled by the instinctive centre, which estimates the condition of the blood at every moment and increases and decreases the rate of respiration accordingly. But we cannot observe this directly. We cannot observe the instinctive centre and its intricate task of attending to the inner work of the organs. But we can observe the results of its work—namely, that after running we breathe more deeply or if we are feverish we breathe more rapidly and realize that this is because the instinctive centre needs more oxygen, and so on. But breathing is not only carried on by the instinct-moving centre. There is an overlapping of control for we can breathe deliberately—that is, voluntarily. A man cannot hold his breath voluntarily beyond a certain time because the instinctive centre will take over his breathing for him as soon as he begins to lose consciousness. But a man can interfere with his breathing and make himself breathe more slowly or more deeply, and so on. This is a dangerous thing to do but there are moments when it is very important and when, in fact, it can save a man's life. If, however, a person tries to control his breathing without understanding what he is doing, and without knowledge, he may interfere with the normal working of the instinct-moving centre, which then becomes lazy, and, as it were, hands over the business of breathing in part. I remember hearing G. say more than once that people who expect to gain increased powers by means of breath-control were fools unless they had gone through long preliminary training under a teacher and had been selected by him. They were fools because they interfered with a function which, once wrongly interfered with long enough, might never work normally afterwards.

The question of the wrong work of centres is a matter of life-long study through self-observation. In order to understand anything you must realize its nature, otherwise you will approach it wrongly or have the wrong attitude to it. You cannot understand about centres and their right and wrong work just in a moment. If you think you can, you will ask the wrong questions and indeed never take in anything about the subject. Think a moment. All your life is a function of, and is controlled by, centres—your thoughts, your feelings, your ideas, your hopes, fears, loves, hates, your actions, your sensations, your pleasures, your comforts, and so on. How, then, can you expect to understand all about right and wrong work of centres in a short time? To do so is like expecting

76

to understand all about life after hearing a lecture or two on it. What has been said so far is only to give you some indication of what is meant and to make you begin to study the subject, and unless you study it by self-observation, then even if you hear a thousand and one lectures on the matter, you will not understand a single thing.

Now it is necessary to give the division of other centres so that people have some general chart to use, to find their way by, and to which they can refer some of their own observations of themselves and find where they belong—for this helps one to see oneself more clearly.

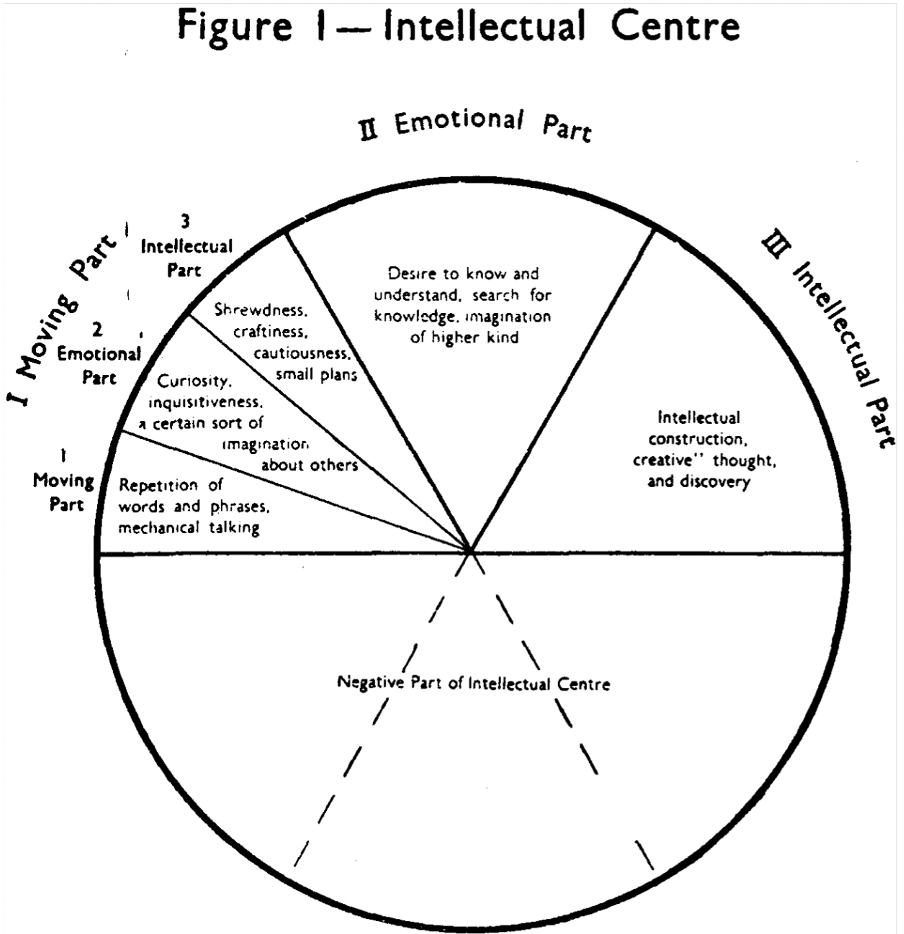

I will now have to divide certain centres into positive and negative divisions, first of all, and then fill in, here and there, at present only some of the subdivisions, giving approximate definitions of their functions. Let us begin with the Intellectual Centre.

Note.—Only the Moving Part of the Intellectual Centre is in any detail charted in this diagram. Note here the difference between Emotional Part of Moving Part of Intellectual Centre and the Emotional Part of Intellectual Centre as a whole. Notice what is meant.

77

78

79

As we said, in these diagrams of the centres and their divisions only a few parts are charted to serve as a guide to the observation of centres and their work. It was part of our work several years ago to observe parts of centres and collect and compare our observations.

All that has been given so far requires careful study. First it is necessary to register what is said about the centres and parts as given and then to think about what it all means and get an individual idea of the subject—for this puts it in higher parts of centres—and then to find examples and try to place them. Please do not ask questions about the parts of centres not mapped out. It is always a sign of negative thinking and automatic questioning which is worse than formatory questioning, to ask about Asia when a lecture is being given on America or to ask about the exception when a rule is being explained.