This is number (25.) of our sequential postings from Volume 1 of Maurice Nicoll’s Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky.

(If you are a subscriber to The Journal of Gurdjieff Studies, you can opt in or out of receiving emails from the Fragments Reading Club category.)

Links to each commentary will be put on the following Contents page, as we progress through the book:

Birdlip, January 3, 1942

COMMENTARY ON EFFORT - Part II.

All through this Work, on every side of it, the effort of remembering must be made. Memory lies in all three centres. Let us suppose a man reaches a state in the Work in which he feels the necessity of making an aim, based on what he has observed in himself. He makes an aim and then decides to keep to it. But in order to keep it, he must remember. He must not merely remember what his aim is, but he must remember why he made it, and what led him to decide to keep it. If he merely remembers his aim as words, as a sentence—namely, that his aim is not to do this or that, not to react in this or that way—for our aims should at first be not to do—it is not enough. He is only remembering in a very small part of the Intellectual Centre. To remember in a real way he must go back and re-create the situation where he made his aim, and think of its meaning and re-feel the circumstances when he decided to keep it, etc. Full memory is a question of all three centres working together and an aim includes all three. For if a man is going to work against something in himself, the thing, whatever it is, will be represented in the Intellectual Centre, and in the Emotional Centre and in the Moving Centre, and keeping the aim will involve all three; and remembering it will also involve all three centres.

In making effort on some side of oneself, such as some particular form of being negative, remember that everything goes in cycles in oneself —that is, everything comes round at certain intervals. It is not that these intervals are regular, but that things recur or return, internally, sometimes sooner, sometimes later. The point is that by observation, a person may notice and remember that this is so, and in this way he may gain some foresight and give himself a shock before some mood, some state in himself has properly begun. This belongs to the idea of making effort at the right time. Once a characteristic state or mood, etc., has gained enough strength, it is difficult or impossible to stop it—i.e. it is too late. But if self-observation has developed that special memory of oneself that results from it (and can only result from it) then if this new memory is strong enough it will give you a point of vantage from where you can make effort upon some useless state, when it is beginning to return. That is, you recognize it. If you really have begun to dislike it, then you will

97

have an emotion to help your memory and thought. This will help and it will also help you to observe more—namely, that the state starts up earlier than you thought, in little trifling things that you had not connected with it before, such as beginning to use certain phrases or in a slight change of feeling to others, and so on.

Fuller observation can help us to recognize states of depression and to distinguish them from negative states. Depression is different from being negative. Try to see the truth of this for yourselves. Observe that it is so. This distinction was particularly emphasized in the last paper, and if you have not observed that depression is different from being negative, then you cannot see what is meant. Being depressed often happens to people who like to think that they are always bright, cheerful and happy. In any case, it is not the same as being negative. Self-observation and memory of one's state of depression are most important, because unless one recognizes depression for what it is one may make the wrong kind of effort. It is only by understanding such states that one can work on them in the right way. Depression is often a result of illness, or rather, when one is ill the possibility of being depressed is present. Being ill lowers the vitality. This is not really depression but is due to the fact that when the Instinctive Centre, which attends to the inner work of the organism and its chemistry, has to meet illness, it borrows from other centres, just as in war money is taken from all kinds of sources. You have all heard that Instinctive Centre borrows usually from the "Bank" of Moving Centre first, then from the Emotional Centre and then from' the Intellectual Centre. But this is not necessarily itself depression ; it is a depressed vitality, and if one is careful to be passive to it and does not identify with it when it begins, if one does not expect any- thing and is quiet and small in oneself, there need be no depression —i.e. loss of hope, and so on—but only a state in which one must not think and has to remain quite still, and silent in oneself. There are, of course, rhythmical alterations in the body which lead to depression. One must learn in illness and in such states of altered vitality to see where one is in oneself and what one can do, what is closed, and what is open. To expect to be as usual when one is ill will make one depressed. This is wrong attitude. To be internally quiet, to stop imagining, to stop complaining, to relax, to realize one is ill and has little available force, is the right approach.

Unlike depression, negative emotion is caused always by another person. The other person need not be present. One has something called imagination which acts instead. Imagination makes us negative —memory makes us negative—but it is always imagination or memory of a person. When the negative emotion arises from imagination or memory it is generally a repetition of what one has felt before about the person in question and after a time it is possible to observe it when it first begins, in which case it can sometimes be separated from before it reaches its full strength. When you are "violently negative", as someone said, it is not possible to do much. Why? Because you do not wish to,

98

and most of us like being violently negative at the moment. You must realize that people love being negative, feeling they suffer, and so on. That is all that can be said. But you have to see it. A great struggle is needed over a long period to begin to dislike being negative. It is so easy to be negative—that is the trouble. Only you yourself, in your deepest thought and understanding and feeling, can extricate yourself from the pit of negative states, by the light of consciousness and aim. One of the most serious negative states can be the result of long-standing self-pity, which especially can lead to loss of the power to make effort. Even the mildest self-pity is negative in colour. It may turn into romance with oneself, but it is negative and has the colour and taste of negative emotion, if one tries to observe it. When my wife and I were in France, G. said : "If you will not pity yourself, I will pity you." A dog, when it is washed, pities itself sometimes. What does it do? It takes advantage—jumps on your bed when it knows it must not. There was a dog in France called "Kakvas"—that is, "like yourself". The thing to realize is that everyone tends to pity himself—rich or poor, married or single, successful or a failure. When a man pities himself, he feels he is owed—like the dog. If you feel that you are owed, you will never begin truly to work on yourself. How could you? You must feel you owe. To make the effort to work on yourself you must actually feel something is wrong with you. It usually takes years and years before a person can even begin to see this with any conviction. The Work has to pass through layer after layer of pride, vanity, ignorance, self- complacency, self-indulgence, self-love, self-merit, and so on. Yet it can penetrate eventually. But before it can, the first sign is usually that a person suddenly begins to realize the Work is talking about something real and shews some sign of thinking about the ideas. The first change is in the mind—i.e. to think differently. This is metanoia—in the Gospels wrongly translated as "repentance". It is called "Driver awakening" in the Work. It begins with realizing one's situation. You must understand that this is not very common. People seldom really think of the Work from themselves—I mean, as if their life depended on it. This is because they do not very often feel that anything is wrong with them, although they are certain others are wrong. It is like the man who became short-sighted and refused to wear glasses, saying there was nothing wrong with him, but that the trouble was that the recent papers were so badly printed. I am speaking of a step people must take.

As long as one thinks in the same way and feels in the same way one is mechanical. One is a machine, you know—but one imagines other- wise. Our life is not action as we imagine, but reaction; and we react to things in the same mechanical way over and over again. It is only by seeing one is a machine, first in this small respect, then in that small respect, that one can get the right emotion to help one to change. Fortunately there is something in us that hates mechanicalness but this is lulled to sleep by our imagination that we are quite conscious and always act from will, and consciousness, and one permanent "I", and

99

always know what we are doing and saying and thinking and so on. It is only by conscious effort that one can realize one's mechanicalness, and this effort must be made towards a definite thing, a definite reaction, something practical and clear and distinct. To take it as a theory is worse than useless. When one realizes one is mechanical in some definite respect, it gives a shock—actually, it is a moment of self-remembering. To work against mechanicalness requires the effort of self-observation. The reason why we react to things in the same mechanical way over and over again is because of the connections and associations in and between our centres. But we are not conscious of this until we observe our centres. In order to change it is necessary to make centres work in a new way. Let us take an example: let us suppose you always get upset when you cannot find something. Is this mechanical or not? Yes, it is a mechanical reaction that will regularly recur unless you put the light of consciousness into it. It is consciousness that changes us. First the effort of self- observation is needed. Suppose you observe that you react by being negative if you cannot find a thing. This is the first effort and this belongs to the general effort of self-observation—that is, of becoming more conscious, of noticing oneself and not always taking oneself for granted. Next, observe your thoughts. What thought comes to you always when you have lost something? Then observe the emotion; notice it, its taste. Then notice your movements, your expression, etc. Next time it will not be so easy to react mechanically when you lose something. What will help you? The work you have done previously on this mechanical reaction—namely, the effort to be more conscious. Everything we do consciously remains for us: everything we do mechanically is lost to us.

***

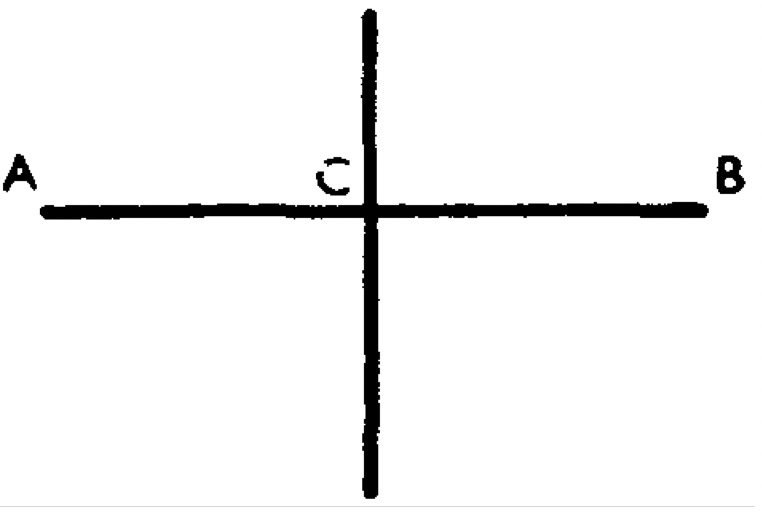

Since we are going to speak about the cosmological side of this Work, I must say something now in preparation about the relationship of conscious effort, or effort in the Work, to mechanical effort, or effort in life. Work is vertical to life. All Work-effort is to lift a man to a higher level, and a higher level is vertical to him—that is, above him. Let us take this symbol, which gives one meaning of the Cross.

The vertical line is a line representing different levels of being, not only of Man, but of the Universe itself. A horizontal line, drawn at right angles, such as AB, and cutting the vertical line at C, will represent a

100

person's life in Time at the level of being represented by the point C. The efforts we make from Cause and Effect in Time—that is, mechanical effort—lie along AB. The vertical line represents a direction of effort different from those made in Time. You have heard that higher states of consciousness are timeless—i.e. without any sense of Time. Movement on the vertical line is timeless. A higher state of a man does not lie along the line AB, but above the man—namely, on the vertical line. This line is what gives meaning to all things. It represents the eternal scale of meaning.

In approaching the cosmological side of this teaching, we have to understand that it is an essential part of the mental apparatus of this system and without it the teaching cannot be rightly formed and connected in the different parts of the mind as an instrument for the reception of the influences coming from higher centres. But I intend to give as much help as possible, in the form of comments, to bring the cosmological side nearer to you so that some of its meaning can begin to influence you. The cosmological side is a very powerful thing, but if no attempt is made to think of it, its force will not affect a person and so he will not feel the Work much beyond his limited self-interests.

Now try to think of this vertical side. We can understand Cause and Effect in Time. In Time Cause always comes before Effect. But Cause is not only in past Time. Cause can be above and below us. In illustration let us take the Table of Cosmoses, from the Earth downwards:

Cosmos of Earth

Cosmos of Organic Life

Cosmos of Man

Cosmos of Cells

Cosmos of Molecules Cosmos of Atoms

You see how Man is not free, because he is a minute part of the Cosmos of Organic Life and he is composed of minute parts belonging to the Cosmos of Cells, which in turn are composed of minute parts—namely, molecules—and so on.

Man is composed of cells, which belong to their own cosmos. But Man is part of Organic Life. If Organic Life dies, Man, who is a part, would die. And if the cosmos below Man—the myriads of cells—dies, Man would cease to exist.

Now this vertical arrangement is permanent. It is, as it were, vertical Cause and Effect. Or you can call it permanent order, or permanent relationship, or the inter-fitting of all things. Whether you say order, permanent arrangement or relationship, etc., does not matter at present. What you have to see is that such a thing as order is not in Time, but that Time moves through order.

Now let me try to shew you how "vertical" Cause can be thought

101

of. If you really begin to think of "vertical" Cause, you will see that there are two sorts and two origins of what we call "Cause". Take, for example, a brick. What is the vertical Cause of a brick?

Builder

|

House

|

Brick

Bricks would not be made unless there were the idea of a house, therefore, in the vertical meaning, the house is the cause of the brick. But in the temporal meaning (horizontal in Time) the brick-kiln is the cause. So it can be represented thus:

The bricks make the house in Time. But the house makes the bricks in the vertical scale of meaning.

Man, as was said, stands like this, in the centre of the Cross. He has vertical meaning and temporal meaning. The temporal cause of Man is the past in Time: vertical cause is his meaning, and his meaning will be the level of being to which he belongs.

You have heard that your level of being attracts your life. This means your life will be according to your level of being. Levels of being can be represented as points in the vertical line and form life by the horizontal line. If your level of being changes, the horizontal line will pass through another point in the vertical line. I want you to take hold of the general principle involved in these illustrations, not to compare them, but to see the idea behind them. We will continue this subject next time.