This is number (34.) of our sequential postings from Volume 1 of Maurice Nicoll’s Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky.

(If you are a subscriber to The Journal of Gurdjieff Studies, you can opt in or out of receiving emails from the Fragments Reading Club category.)

Links to each commentary will be put on the following Contents page, as we progress through the book:

Birdlip, May 18, 1942

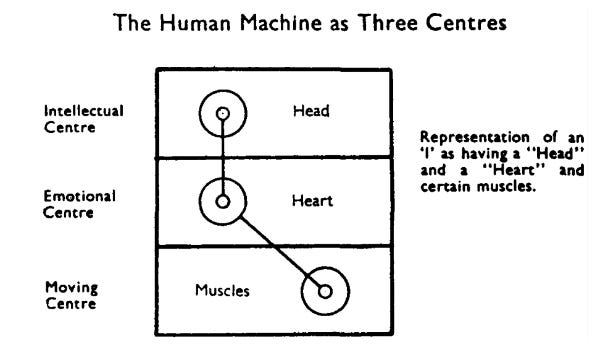

We will now speak of the observation of connections between centres in the form of 'I's. As you know, this Work begins with self-observation because the subject of it is this invisible thing called "oneself" which we usually take for granted and which can only be observed by each person individually. The first thing is to realize that you are not one and the same person either at different moments or at the same moment. In the first practice of self-observation you are told to observe that you have quite different centres or minds in you which work simultaneously. You have thoughts, emotions and movements, taking only these three centres, namely, the Intellectual Centre, the Emotional Centre and the Moving Centre. They are three utterly different things. Now every person is a meeting-house of 'I's. The different 'I's in you have their representation in all these three centres in more or less degree. That is, every 'I' in you has its representation in these three different minds or centres, and so appears quite differently in each centre—in fact, so differently that it takes a long time before we can trace the manifestation of an 'I' in all these three forms of it.

Although other centres exist, let us speak of the Intellectual, Emotional and Moving Centres. Every 'I' in a man is represented in these three centres.

136

In trying to control an observed 'I', you must remember that it is something that thinks, and feels and moves—that is, each representation of it in each centre is different. The control of the human machine is difficult therefore because everything that is formed in it psychologically—namely, as an 'I'—is represented in three entirely different ways, that seem at first sight unconnected. For example, you frown. This is in Moving Centre. But this frowning is represented in the Emotional Centre as a feeling, and it is represented in the Intellectual Centre as a thought or a gramophone record—that is, a series of thoughts going round and round mechanically. Full observation of an 'I' is the observation of it in all the three centres of its origin simultaneously.

Let us now find an example for general discussion. Let us take "Worrying".

QUESTION: What is worry? Does the Work say anything about worrying? How can it be stopped?

ANSWER: Worry is a form of identifying. Literally, the word has the meaning of tearing and twisting, or choking and strangling; it was originally connected with the word 'wring', which is still used in the expression 'wringing one's hands', one of the outward signs of worry. You will remember that every psychological or inner state finds some outer representation via the moving centre—that is, it is represented in some particular muscular movements or contractions, etc. You may have noticed that a state of worry is often reflected by a contracted wrinkling of the forehead or a twisting of the hands. States of joy never have this representation. Negative states, states of worry, or fear, or anxiety, or depression, represent themselves in the muscles by contraction, flexion, being bowed down, etc. (and often, also, by weakness in the muscles), whereas opposite emotional states are reflected into the moving centre as expansion, as standing upright, as extension of the limbs, relaxing of tension, and usually by a feeling of strength. To stop worry, people who worry and thereby frown too much or pucker up and corrugate their foreheads, clench their fists, almost cease breathing, etc., should begin here—by relaxing the muscles expressing the emotional state, and freeing the breath. Relaxing in general has behind it, esoterically speaking, the idea of preventing negative states. Negative states are less able to come when a person is in a state of relaxation. That is why it is said so often that it is necessary to practise relaxing every day, by passing the attention over the body and deliberately relaxing all tense muscles.

Control of the emotional centre is difficult directly, partly because it works so quickly—30,000 times more quickly than the formatory part of the intellectual centre, so that a man gets worried or negative before he knows it. But the emotional centre is sometimes in the Work compared with an uncontrolled rogue elephant with two controlled elephants on either side of it—namely, the intellectual centre and the moving centre. Wrong emotional states, habitual bad states of worry, crossness, etc. must first be noticed as existing in one. As a rule people do not see their states but are them. Next, one of the controlled elephants must be

137

used. Let us consider what it means to use the intellectual centre in this respect. This means that you must notice the thoughts that are going on when you are worrying. We have a certain amount of will over the intellectual centre—that we can control thought to a small extent. By stopping, or not going with, not believing in, not consenting to, the thought-part of worrying, one elephant, so to speak, is brought alongside the uncontrolled emotional centre. The other controllable elephant is the moving centre, over which we have will if we direct attention to it. We can relax muscles and so on. As you know, in the directions given in the Work about relaxing, it is said first that the small muscles must be relaxed—the small muscles of the face, the muscles of expression, particularly. This includes the eye-muscles, the muscles round the mouth and chin, the tongue and throat and scalp muscles, and so on.

To return to worrying. Worrying is the wrong work of centres. It is always useless. It is a form of inner considering—i.e. of identifying. It is a continual mixing up of negative imagination with a few facts and so makes only wrong connections in centres. It is a sort of lying, among the many other kinds of lying that go on in us and mess up the centres. It is always easy to worry, as it gives a relief and is, as it were, a form of justifying oneself. It is close to self-pity and violence. Worrying is not thinking. The mind is driven by the worry, by the emotional state, and is obscured. Attention to anything always helps, for directed attention puts us into more conscious parts of centres. Worrying is not thinking of others. It is not external considering. It is mixed up with oneself and this takes a long time to observe distinctly. In learning how to live from the Work point of view, so that we live more consciously in life, or live in the Work in life and not just in life without anything between us and life, worrying is one of the things that shew us something about ourselves if we notice it uncritically and over a long enough period. But you must not think that the opposite of worrying is indifference. You can and should feel 'anxiety' about another person in danger—a mixture of hope and fear—but worrying is quite different, for then the imagination comes in. It becomes a habit, just as do so many other negative states, and people even imagine they are better than others by having them and feel merit in worrying. People even think it is right to worry about everything, about the past and the future, about themselves, about others, and so on. This is simply nothing but a serious negative illness, difficult to cure, for once a person has become nothing but an inverted machine for worrying, all sorts of wrong connections have been established and everything works in the wrong way, and since the only thing he enjoys is worrying, to deprive him of this, were it possible, would be to destroy his chief interest. In this connection, you will remember one of the Work sayings—that you are asked above all to do one thing, to give up your particular form of suffering. This sounds easy. Try it. The reason why it is so difficult is because to do so is to destroy whole systems of 'I's in yourself that enjoy making you suffer and that you think you are.

138

To return to the question: what is worrying? Since it is a form of identifying, it means that it brings about a continual loss of force. People who worry a great deal exhaust themselves, drain themselves of force. If you will notice yourself when you are worrying, you will see that it really is like tearing and twisting and strangling oneself inside, corresponding with the outer muscular movements which have already been described. There is no centre of gravity. There is no direction, no clear aim; everything is in disorder; everything is, as it were, running about in oneself in every direction. It is as if all the different 'I's in oneself got up and rushed about wringing their hands and saying anything that the negative imagination, which dominates the scene, suggests to them. I am not saying that it is possible never to worry. There are situations, especially to-day, where it is well-nigh impossible to stop it at times. I am speaking more of habitual tendencies to worry about everything and take every event as a source of worry. To formulate clearly what one is going to do—to have some direction—helps to prevent this state of disorder, which is, as said, a form of internal considering and is not external considering. Internal considering is always mechanical. External considering is always conscious—it is consciously putting yourself in another person's position and since this requires directed attention, it takes you out of worrying. If you notice, you will see that little forms of worrying start very early in the morning. It is a very good thing, which is worth doing, to work on oneself in the early morning, before, as it were, descending into life and duty. A little conscious work at that time, noticing the small beginnings of worrying or negative thoughts or self-pity, etc., etc. and saying no to them—lifting oneself out of them—not taking them as you—all this work on non-identifying with certain machines, certain 'I's, in the early morning, can alter the whole day. And to this, of course, belongs the idea of cancelling debts, letting go all inner accounts—if possible. Then something fresh and new begins the day, and the staleness of life is prevented which is really the staleness of oneself always reacting in the same way to everything, always having the same views, always taking others in the same way, and so on. Work on yourself can have marvellous results—if you remember you are in life in the Work and not in life without anything between you and it. The Work is to transform your relations to life. All the practical things said in it have this object. This is to work on oneself. That is, it is to be in the Work, in life—not in life. What is your task? Why are you down here? What is it that you have to change? What is it that you have to learn about yourself, this thing you take for granted, this thing that is your apparatus for living? Does your apparatus for living give you the results you wish for? Yourself, your personality, is the apparatus you are using for living life. It is good to begin to see that your way of taking life is your life—and that you can begin to work on your way of taking it—and that means working on yourself and your mechanical reactions to all that happens. For your mechanical reactions to life are yourself and that makes your unhappiness and happiness and this thing called yourself

139

is the apparatus for living life that you have made and which has been made in you by thousands of forgotten causes. This is the thing we wheel out every morning to face the day with. And this is the thing the Work speaks of in all its stages—the thing that you can work upon and alter. Try to think that it is not life you can change, but yourself in your reaction to life. This is where the first idea of what it means to work on oneself lies. Once you see the idea, then, whatever the conditions of life, you have a power in your grasp whose value is beyond price. You have begun to grasp the pearl, to see what life on earth really means. For a long time we absorb every kind of negative emotion, identifying with it and taking it as ourselves, as necessary, as true, and try to work on it once it has formed itself. But the time comes when it cannot form itself. Now the effect of not going with some mechanical reaction in yourself and feeling you are free in respect of it is quite magical. You will notice what happens. It is very interesting, but it is a matter of your own experience. You will perhaps grasp that the Work is not mere dull labour. It is self-freeing through a peculiar inner effort, which is called work on oneself.