(56.) Maurice Nicoll 1 - The Four Bodies of Man (III), The Four Ways - p.231-5

This is number (56.) of our sequential postings from Volume 1 of Maurice Nicoll’s Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky.

(If you are a subscriber to The Journal of Gurdjieff Studies, you can opt in or out of receiving emails from the Fragments Reading Club category.)

Links to each commentary will be put on the following Contents page, as we progress through the book:

Birdlip, January 23, 1943

THE FOUR BODIES OF MAN - PAPER III—THE FOUR WAYS

Mr. Ouspensky is speaking throughout this chapter.

At the next meeting G. began where he had left off the time before.

"I said last time," he said, "that immortality is not a property with which Man is born. But Man can acquire immortality. All existing and generally known ways to immortality can be divided into three categories:

1. The way of the Fakir,

2. The way of the Monk,

3. The way of the Yogi.

The way of the fakir is the way of struggle with the physical body, the way of work in the first room. This is a long, difficult and uncertain way. The fakir strives to develop physical will, power over the body. This is attained by means of terrible sufferings, by torturing the body. The whole way of the fakir consists of various incredibly difficult physical exercises. The fakir either stands motionless in the same position for hours, days, months or years; or sits with outstretched arms on a bare stone in sun, rain and snow; or tortures himself with fire, puts his legs into an ant-heap and so on. If he does not fall ill and die before what may be called physical will is developed in him, then he attains the fourth room or the possibility of forming the fourth body. But his other functions—emotional, intellectual and so forth—remain undeveloped. He has acquired will but he has nothing to which he can apply it; he cannot make use of it for gaining knowledge or for self-perfection. As a rule he is too old to begin new work.

But where there are schools of fakirs there are also schools of yogis. Yogis generally keep an eye on fakirs. If a fakir attains what he has aspired to before he is too old, they take him into a yogi school, where first they heal him and restore his power of movement, and then begin to teach him. A fakir has to learn to walk and to speak like a baby. But he now possesses a will which has overcome incredible difficulties on his way and this will may help him to overcome the

232

difficulties on the second part of the way, the difficulties, namely, of developing the intellectual and emotional functions.

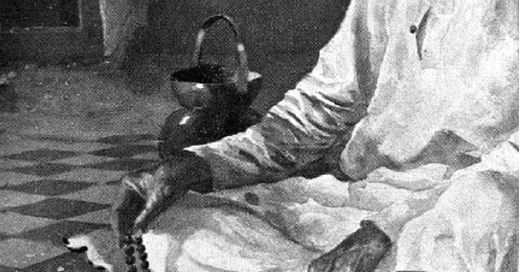

You cannot imagine what hardships fakirs undergo. I do not know whether you have seen real fakirs or not. I have seen many: for instance I saw one in the inner court of a temple in India and I even slept near him. Day and night for twenty years he had been standing on the tips of his fingers and toes. He was no longer able to straighten himself. His pupils carried him from one place to another, took him to the river and washed him like some inanimate object. But this was not attained all at once. Think what he had to overcome, what torture he must have suffered in order to get to that stage.

And a man becomes a fakir not because he understands the possibilities and the results of this way, and not because of religious feeling. In all Eastern countries where fakirs exist there is a custom among the common people of promising to give to fakirs a child born after some happy event. Besides this, fakirs often adopt orphans, or simply buy little children from poor parents. These children become their pupils and imitate them, some only outwardly, but some afterwards become fakirs themselves.

In addition to these, other people become fakirs simply from being struck by some fakir they may have seen. Near every fakir in the temples people can be seen who imitate him, who sit or stand in the same posture—not for long of course, but still, occasionally for several hours. And sometimes it happens that a man who went into the temple accidentally on a feast-day, and began to imitate some fakir who particularly struck him, does not return home any more but joins the crowd of that fakir's disciples and later, in the course of time, becomes a fakir himself. You must understand that I take the word 'fakir' in inverted commas. In Persia Fakir simply means a beggar; and in India a great many jugglers call themselves fakirs. And Europeans, particularly learned Europeans, very often give the name of fakir to yogis, as well as to monks of various wandering orders. But in reality the way of fakir, the way of monk and the way of the yogi are entirely different. So far I have spoken of fakirs. This is the First Way.

The Second Way is the way of the monk. This is the way of devotion to faith, the way of religious feeling, religious sacrifices. Only a man with very strong religious emotions and a very strong religious imagination can become a 'monk' in the true sense of the word. The way of the monk also is very long and hard. A monk spends years and tens of years struggling with himself, but all his work is concentrated on the 'second room', on the second body, that is, on feelings. Subjecting all his other emotions to one emotion, that is, devotion to his faith, he develops unity in himself as will over the emotions, and in this way reaches the 'fourth room'. But his physical body and his thinking capacities may remain entirely undeveloped. In order to be able to make use of what he has attained, he must develop the use and control of his body and his capacity to think. This can only be achieved by means of fresh sacrifices,

233

fresh hardships, fresh renunciations. That is, a monk has to become a yogi and a fakir: and very few get as far as this.

The Third Way is the way of the yogi. This is the way of knowledge, the way of mind. The way of the yogi consists in working in the 'third room' and in striving to enter the 'fourth room' by means of knowledge. The yogi reaches the 'fourth room' by developing his mind and the control of his thoughts, but his body and emotions may remain undeveloped in a corresponding way and, like the fakir and the monk, he may be unable to make use of the results of his attainments. In his case, however, he has the advantage of understanding his position, of knowing what he lacks, what he must do and in what direction he must go.

But all the ways, the way of the fakir as well as the way of the monk and the way of the yogi, have one thing in common. They all begin with the most difficult thing, with a complete change of life, with a renunciation of all worldly things. A man must give up his home, his family, his friends, renounce all the pleasures, attachments and duties of life and go out into the desert, or into a monastery or a yogi school. From the very first day, from the very first step on his way, he must die to the world; only thus can he hope to attain anything in one of these ways.

The Fourth Way is different from the three Ways already considered because the Fourth Way requires no retirement into the desert, nor does it require a man to give up and renounce everything by which he formerly lived. The Fourth Way begins much further on than does the way of the Yogi. This means that a man must be prepared for the Fourth Way and this preparation embraces many different sides and takes a long time. Furthermore a man must be living in conditions favourable for work in the Fourth Way, or, in any case, in conditions which do not render it impossible. It must be understood that both in the inner and in the external life of a man there may be, conditions which create insuperable barriers to the Fourth Way. Furthermore, the Fourth Way has no definite forms like the ways of the fakir, the monk and the yogi. First of all, it has to be found. This is the first test. At the same time, the beginning of the Fourth Way is easier than the beginning of the ways of the fakir, the monk and the yogi. In the Fourth Way it is possible to work and to follow this way while remaining in the usual conditions of life, continuing to do the usual work, preserving former relations with people, and without renouncing or giving up anything. On the contrary, the conditions of life in which a man is placed at the beginning of his work, in which, so to speak, the Work finds him, are the best possible for him, at any rate at the beginning of the work. These conditions are natural for him. These conditions are the man himself, because a man's life and its conditions correspond to what he is. Any conditions different from those created by life would be artificial for a man and in such artificial conditions the Work would not be able to touch every side of his being at once.

Thanks to this the Fourth Way affects simultaneously every side of a man's being. It is work in the three rooms at once. The fakir works in the

234

first room, the monk in the second, the yogi in the third. On reaching the fourth room the fakir, the monk and the yogi leave behind them many things unfinished, and they cannot make full use of what they have attained because they are not masters of all their functions. The fakir is master of his body but not of his emotions or his mind, which remain undeveloped; the monk is master of his emotions but not of his body or his mind; the yogi is master of his mind but not of his body or his emotions.

Then again the Fourth Way differs from the other ways in that the principal demand made upon a man in it is the demand for understanding. A man must do nothing that he does not understand, except as an experiment under the supervision and direction of a teacher. In the Fourth Way the more a man understands what he is doing the greater will be the results of his efforts. This is a fundamental principle of the Fourth Way. The results of work in it are in proportion to the consciousness and understanding of the Work. No 'faith' is required in the Fourth Way; on the contrary faith of any kind is opposed to the Fourth Way. In the Fourth Way a man must see for himself. He must satisfy himself of the truth of what he is told. And until he is satisfied he must do nothing.

The method of the Fourth Way consists in doing something in one room and simultaneously doing something corresponding to it in the other two rooms—that is to say, while working on the physical body to work simultaneously on the mind and the emotions, and while working on the mind to work on the physical body and the emotions, and while working on the emotions to work on the mind and the physical body. This can be achieved, thanks to the fact that in the Fourth Way it is possible to make use of certain knowledge inaccessible to the ways of the fakir, the monk and the yogi. This knowledge makes it possible to work in three directions simultaneously. A whole parallel series of physical, mental and emotional efforts and exercises serves this purpose. In addition, in the Fourth Way it is possible to individualize the work of each separate person—that is to say, each person can only do what is necessary and not what is useless for him. This is due to the fact that the Fourth Way dispenses with a great deal of what is superfluous and preserved simply through tradition in the other ways.

So that when a man attains will in the Fourth Way he can make use of it because he has acquired the necessary development and control of bodily, emotional and intellectual functions as well. And besides, he has saved a great deal of time by working on the three sides of his being in a parallel way and simultaneously.

The Fourth Way is sometimes called the way of the sly man. The 'sly man' knows some secret which the fakir, monk and yogi do not know. How the 'sly man' learned this secret—is his secret. Perhaps he found it in some old book, perhaps he inherited it, perhaps he bought it, perhaps he stole it from someone. It makes no difference. The 'sly man' knows the secret and with its help outstrips the fakir, the monk and the yogi.

235

Of the four the fakir acts in the crudest manner; he knows very little and understands very little. Let us suppose that by a whole month of intense torture he develops in himself a certain energy, a certain substance which produces certain changes in him. He does it absolutely blindly, with his eyes shut, knowing neither aim, methods nor results, simply in imitation of others.

The monk knows what he wants a little better; he is guided by religious feeling, by a desire for achievement, for salvation; he trusts his teacher who tells him what to do, and he believes that his efforts and sacrifices are 'pleasing to God'. Let us suppose that a week of fasting, continual prayer, privations and so on, enables him to attain what the fakir develops in himself by a month of self-torture.

The yogi knows considerably more. He knows what he wants, he knows why he needs it, he knows how it can be acquired. He knows, for instance, that it is necessary for his purpose to produce a certain substance in himself. He knows that this substance can be produced in one day by certain kinds of mental exercises, or concentration of consciousness. So he keeps his attention on these exercises for a whole day without allowing himself a single outside thought, and he obtains what he needs. In this way a Yogi spends on the same thing only one day compared with a month spent by the fakir and a week spent by the monk.

But in the Fourth Way knowledge is still more exact and perfect. A man who follows the Fourth Way knows quite definitely what substances he needs for his aims and he knows that these substances can be produced within the body by a month of physical suffering, by a week of emotional strain or by a day of mental exercises—and also, that they can be introduced into the organism from without if it is known how to do it. And so, instead of spending a whole day in exercises like the Yogi, a week in prayer like the monk, or a month in self-torture life the fakir, he simply prepares and swallows a little pill which contains all the substances he wants and, in this way, without loss of time, he obtains the required results.

It must be noted further," said G., "that in addition to these proper and legitimate Ways, there are also artificial ways which give temporary results only, and also wrong ways which may even give permanent results. In these ways a man also seeks the key to the fourth room and sometimes finds it. But what he finds in the fourth room is not yet known. It also happens that the door to the fourth room is opened artificially with a skeleton key. And in both these cases the room may prove to be empty."

With this G. stopped.