This is this is the forty-ninth of our weekly readings in Fragments Reading Club from P.D. Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous, where we are gradually working our way through the whole book. Please post comments and questions.

See this link for the beginning of the book.

The Current list of posts in Fragments Reading Club is updated regularly, for handy navigation.

(If you are a subscriber to The Journal of Gurdjieff Studies, you can opt in or out of receiving emails from the Fragments Reading Club category.)

G.'s apartment. Reactions to silence. "Seeing lies." A demonstration. How to awake? How to create the emotional state necessary? Three ways. The necessity of sacrifice. "Sacrificing one's suffering." Expanded table of hydrogens. A "moving diagram." A new discovery. "We have very little time."

In October I was with G. in Moscow.

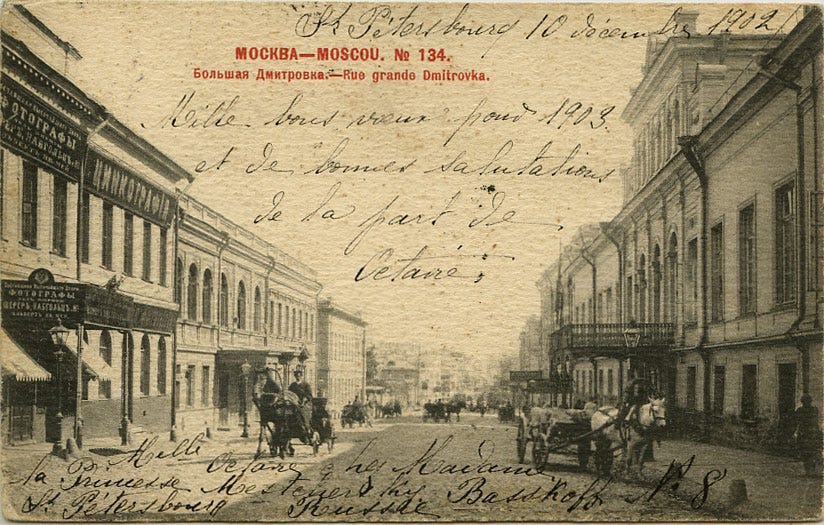

His small apartment on the Bolshaia Dmitrovka, all the floors and walls of which were covered in the Eastern style with carpets and the ceilings hung with silk shawls, astonished me by its special atmosphere. First of all the people who came there—who were all G.'s pupils—were not afraid to keep silent. This alone was something unusual. They came, sat down, smoked, they often did not speak a single word for hours. And there was nothing oppressive or unpleasant in this silence; on the contrary, there was a feeling of assurance and of freedom from the necessity of playing a forced and invented role. But on chance and curious visitors this silence produced an extraordinarily strange impression. They began to talk and they talked without stopping as if they were afraid of stopping and feeling something. On the other hand others were offended, they thought that the "silence" was directed against them in order to show them how much superior G.'s pupils were and to make them understand that it was not worth while even talking to them; others found it stupid, amusing, "unnatural," and that it showed our worst features, particularly

272

our weakness and our complete subordination to G. who was "oppressing us."

P. even decided to make notes of the reactions of various types of people to the "silence." I realized in this place that people feared silence more than anything else, that our tendency to talk arises from self-defense and is always based upon a reluctance to see something, a reluctance to confess something to oneself.

I quickly noticed a still stranger property of G.'s apartment. It was not possible to tell lies there. A lie at once became apparent, obvious, tangible, indubitable. Once there came an acquaintance of G.'s whom I had met before and who sometimes came to G.'s groups. Besides myself there were two or three people in the apartment. G. himself was not there. And having sat a while in silence our guest began to tell how he had just met a man who had told him some extraordinarily interesting things about the war, about possibilities of peace and so on. And suddenly quite unexpectedly for me I felt that he was lying. He had not met anybody and nobody had told him anything. He was making it all up on the spot simply because he could not endure the silence.

I felt awkward looking at him. It seemed to me that if I looked at him he would realize that I saw that he was lying. I glanced at the others and saw that they felt as I did and were barely able to repress their smiles. I then looked at the one who was talking and I saw that he alone noticed nothing and he continued to talk very rapidly, becoming more and more carried away by his subject and not at all noticing the glances that we unintentionally exchanged with one another.

This was not the only case. I suddenly remembered the attempts we made in the summer to describe our lives and the "intonations" with which we spoke when we tried to hide facts. I realized that here also the whole thing was in the intonations. When a man is chattering or simply waiting for an opportunity to begin he does not notice the intonations of others and is unable to distinguish lies from the truth. But directly he is quiet himself, that is, awakes a little, he hears the different intonations and begins to distinguish other people's lies.

We spoke several times with G.'s pupils on this subject. I told them what had happened in Finland and about the "sleeping people" I had seen on the streets of St. Petersburg. The feeling of mechanical lying people here in G.'s apartment reminded me very much of the feeling of "sleeping people."

I wanted very much to introduce some of my Moscow friends to G., but from among all those whom I met during these days only one, my old newspaper friend V. A. A., produced the impression of being sufficiently alive, although he was as usual overloaded with work and rushing from one place to another. But he was very interested when I told him about G. and with G.'s permission I invited him to have lunch at G.'s place.—

273

G. summoned about fifteen of his people and arranged a lunch which, at that time, was luxurious, with zakuski, pies, shashlik, Khaghetia wine, and so on, in a word it was one of those Caucasian lunches that begin at midday and last until the evening.—He seated A. near him, was very kind to him, entertained him all the time, and poured out wine for him. My heart suddenly fell when I realized to what a test I had brought my old friend. The fact was that everyone kept silence. A. held out for five minutes. Then he began to talk. He spoke of the war, of all our allies and enemies together and separately; he communicated the opinions of all the public men of Moscow and St. Petersburg upon all possible subjects; then he talked about the desiccation of vegetables for the army (with which he was then occupied in addition to his journalistic work), particularly the desiccation of onions, then about artificial manures, agricultural chemistry, and chemistry in general; about "melioration"; about spiritism, the "materialization of hands," and about what else I do not remember now. Neither G. nor anyone else spoke a single word. I was on the point of speaking fearing that A. would be offended, but G. looked at me so fiercely that I stopped short. Besides, my fears were in vain. Poor A. noticed nothing, he was so carried away by his own talk and his own eloquence that he sat on happily at the table and talked without stopping for a moment until four o'clock. Then with great feeling he shook hands with G. and thanked him for his "very interesting conversation." G., looking at me, laughed slyly.

I felt very ashamed. They had made a fool of poor A. He certainly could not have expected anything of the kind, so he was caught. I realized that G. had given a demonstration to his people.

"There, you see," he said, when A. had gone. "He is called a clever man. But he would not have noticed it even if I had taken his trousers off him. Only let him talk. He wants nothing else. And everybody is like that. This one was much better than many others. He told no lies. And he really knew what he talked about, in his own way of course. But think, what use is he? He is no longer young. And perhaps this was the one time in his life when there was an opportunity of hearing the truth. And he talked himself all the time."

Of the Moscow talks with G. I remember one which is connected with another talk in St. Petersburg I have already given.

This time G. himself began to speak.

"What do you find is the most important thing of all you have learned up to now?" he asked me.

"The experiences, of course, which I had in August," I said. "If I were able to evoke them at will and use them, it would be all that I could wish for because I think that then I should be able to find all the rest. But at the same time I know that these 'experiences,' I choose this word

274

only because there is no other, but you understand of what I speak"—he nodded— "depended on the emotional state I was in then. And I know that they will always depend on this. If I could create such an emotional state in myself I should very quickly come to these experiences. But I feel infinitely far from this emotional state, as though I were asleep. This is 'sleep' that was being awake.—How can this emotional state be created? Tell me."

"There are three ways," said G. "First, this state can come by itself, accidentally. Second, someone else can create it in you. And third, you can create it yourself. Which do you prefer?"

I confess that for a second I had a very strong desire to say that I preferred someone else, that is, him, to create in me the emotional state of which I was speaking. But I at once realized that he would say that he had already done it once and that now I ought either to wait until this came itself or that I ought to do something myself to get it.

"I want of course to create it myself," I said. "But how can it be done?"

"I have already said before that sacrifice is necessary," said G. "Without sacrifice nothing can be attained. But if there is anything in the world that people do not understand it is the idea of sacrifice. They think they have to sacrifice something that they have. For example, I once said that they must sacrifice 'faith,' 'tranquillity,' 'health.' They understand this literally. But then the point is that they have not got either faith, or tranquillity, or health. All these words must be taken in quotation marks. In actual fact they have to sacrifice only what they imagine they have and which in reality they do not have. They must sacrifice their fantasies. But this is difficult for them, very difficult. It is much easier to sacrifice real things.

"Another thing that people must sacrifice is their suffering. It is very difficult also to sacrifice one's suffering. A man will renounce any pleasures you like but he will not give up his suffering. Man is made in such a way that he is never so much attached to anything as he is to his suffering. And it is necessary to be free from suffering. No one who is not free from suffering, who has not sacrificed his suffering, can work. Later on a great deal must be said about suffering. Nothing can be attained without suffering but at the same time one must begin by sacrificing suffering. Now, decipher what this means."

I stayed in Moscow about a week and returned to St. Petersburg with a fresh store of ideas and impressions. Here a very interesting occurrence took place which explained many things to me in the system and in G.'s methods of instruction.

During the period of my stay in Moscow G.'s pupils had explained to me various laws relating to man and the world; among others they showed me again the "table of hydrogens," as we called it in St. Petersburg, but

275

in a considerably expanded form. Namely, besides the three scales of "hydrogens" which G. had worked out for us before, they had taken the reduction further and had made in all twelve scales. (See Table 4.)

In such a form the table was scarcely comprehensible. I was not able to convince myself of the necessity of reduced scales.

"Let us take for instance the seventh scale," said P. "The Absolute here is 'hydrogen' 96. Fire can serve as an example of 'hydrogen' 96. Fire then is the Absolute for a piece of wood. Let us take the ninth scale. Here the Absolute is 'hydrogen' 384 or water. Water will be the Absolute for a piece of sugar."

But I was unable to grasp the principle on the basis of which it would be possible to determine exactly when to make use of such a scale. P. showed me a table made up to the fifth scale and relating to parallel levels in different worlds. But I got nothing from it. I began to think whether it was not possible to unite all these various scales with the various cosmoses. And having dwelt on this thought I went in an absolutely wrong direction because the cosmoses of course had no relation whatever to the division of the scale. It seemed to me at the same time that I had in general ceased to understand anything in the "three octaves of radiations" from which the first scale of "hydrogens" was deduced. The principal stumbling block here was the relation of the three forces 1, 2, 3 and 1, 3, 2 and the relations between "carbon," "oxygen," and "nitrogen."

At the same time I realized that this contained something important. And I left Moscow with the unpleasant feeling that not only had I not acquired anything new but that I seemed to have lost the old, that is, what I thought I had already understood.

We had an agreement in our group that whoever went to Moscow and heard any new explanations or lectures must, on his arrival in St. Petersburg, communicate it all to the others. But on the way to St. Petersburg while going carefully in my head through the Moscow talks, I felt that I would not be able to communicate the principal thing because I did not understand it myself. This irritated me and I did not know what I was to do. In this state I arrived at St. Petersburg and on the following day I went to our meeting.

Trying to draw out as much as possible the beginning of the "diagrams," as we called a part of G.'s system, dealing with general questions and laws, I began to convey the general impressions of my journey. And all the time I was saying one thing, in my head another thing was running: How shall I begin—what does the transition 1, 2, 3 into 1, 3, 2 mean? Can an example of such a transition be found in the phenomena we know?

I felt that I must find something now, immediately, because unless I found something myself first I could say nothing to the others.

276

277

I began to draw the diagram on the board. It was the diagram of radiations in three octaves: Absolute-sun-earth-moon. We were already accustomed to this terminology and to G.'s form of exposition. But I did not know at all what I would say beyond what they knew already.

And suddenly a single word, which came into my head and which no one had pronounced in Moscow, connected and explained everything: "a moving diagram." I realized that it was necessary to imagine this diagram as a moving one, all the links in the chain changing places as in some mystical dance.

I felt so much in this word that for some time I did not hear myself what I was saying. But after I had collected my thoughts I saw that they were listening to me and that I had explained everything I had not understood myself on the way to the meeting. This gave me an extraordinarily strong and clear sensation as though I had discovered for myself new possibilities, a new method of perception and understanding by giving explanations to other people. And under the impetus of this sensation, as soon as I had said that examples or analogies of the transition of the forces 1, 2, 3 and 1, 3, 2 must be found in the real world, I at once saw these examples both in the human organism and in the astronomical world and in mechanics in the movements of waves.

I afterwards had a talk with G. about various scales, the purpose of which I did not understand.

"We waste time on guessing riddles," I said. "Would it not be simpler to help us to solve these more quickly? You know that before us there are many other difficulties, we shall never even reach them going at this pace. You yourself have said, and very often, that we have very little time."

"It is precisely because there is little time and because there are many difficulties ahead that it is necessary to do as I am doing," said G. "If you are afraid of these difficulties, what will it be like later on? Do you think that anything is given in a completed form in schools? You look at this very naïvely. You must be cunning, you must pretend, lead up to things in conversation. Sometimes things are learned from jokes, from stories. And you want everything to be very simple. This never happens. You must know how to take when it is not given, to steal if necessary, but not to wait for somebody to come and give it to you."

[End of chapter]