This is the nineteenth of our weekly readings in Fragments Reading Club from P.D. Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous, where we are gradually working our way through the whole book. Please post comments and questions.

See this link for the beginning of the book.

(If you are a subscriber to The Journal of Gurdjieff Studies, you can opt in or out of receiving emails from the Fragments Reading Club category.)

Talk about aims. Can the teaching pursue a definite aim? The aim of existence. Personal aims. To know the future. To exist after death. To be master of oneself. To be a Christian. To help humanity. To stop wars. G.'s explanations. Fate, accident, and will. "Mad machines." Esoteric Christianity. What ought man's aim to be? The causes of inner slavery. With what the way to liberation begins.

Chapter Six

ONE of the next lectures began with a question asked by one of those present: What was the aim of his teaching?

“I certainly have an aim of my own,” ’ said G. “But you must permit me to keep silent about it. At the present moment my aim cannot have any meaning for you, because it is important that you should define your own aim. The teaching by itself cannot pursue any definite aim. It can only show the best way for men to attain whatever aims they may have. The question of aim is a very important question. Until a man has defined his own aim for himself he will not be able even to begin ‘to do’ anything. How is it possible ‘to do’ anything without having an aim? Before anything else ‘doing’ presupposes an aim.”

“But the question of the aim of existence is one of the most difficult of philosophical questions,” said one of those present. “You want us to begin by solving this question. But perhaps we have come here because we are seeking an answer to this question. You expect us to have known it beforehand. If a man knows this, he really knows everything.”

“You misunderstood me,” said G. “I was not speaking of the philosophical significance of the aim of existence. Man does not know it and he cannot know it so long as he remains what he is, first of all, because there is not one but many aims of existence. On the contrary, attempts to answer this question using ordinary methods are utterly hopeless and useless. I was asking about an entirely different thing. I was asking about your personal aim, about what you want to attain, and not about the reason for your existence. Everyone must have his own aim: one man wants riches, another health, a third wants the kingdom of heaven, the fourth wants to be a general, and so on. It is about aims of this sort that I am asking. If you tell me what your aim is, I shall be able to tell you whether we are going along the same road or not.

“Think of how you formulated your own aim to yourselves before you came here.”

“I formulated my own aim quite clearly several years ago,” I said. “I said to myself then that I want to know the future. Through a theoretical study of the question I came to the conclusion that the future can be known, and several times I was even successful in experiments in knowing

100

the exact future. I concluded from this that we ought, and that we have a right, to know the future, and that until we do know it we shall not be able to organize our lives. A great deal was connected for me with this question. I considered, for instance, that a man can know, and has a right to know, exactly how much time is left to him, how much time he has at his disposal, or, in other words, he can and has a right to know the day and hour of his death. I always thought it humiliating for a man to live without knowing this and I decided at one time not to begin doing anything in any sense whatever until I did know it. For what is the good of beginning any kind of work when one doesn’t know whether one will have time to finish it or not?”

“Very well,” said G., “to know the future is the first aim. Who else can formulate his aim?”

“I should like to be convinced that I shall go on existing after the death of the physical body, or, if this depends upon me, I should like to work in order to exist after death,” said one of the company.

“I don’t care whether I know the future or not, or whether I am certain or not certain of life after death,” said another, “if I remain what I am now. What I feel most strongly is that I am not master of myself, and if I were to formulate my aim, I should say that I want to be master of myself.”

“I should like to understand the teaching of Christ, and to be a Christian in the true sense of the term,” said the next.

“I should like to be able to help people,” said another.

“I should like to know how to stop wars,” said another.

“Well, that’s enough,” said G., “we have now sufficient material to go on with. The best formulation of those that have been put forward is the wish to be one’s own master. Without this nothing else is possible and without this nothing else will have any value. But let us begin with the first question, or the first aim.

“In order to know the future it is necessary first to know the present in all its details, as well as to know the past. Today is what it is because yesterday was what it was. And if today is like yesterday, tomorrow will be like today. If you want tomorrow to be different, you must make today different. If today is simply a consequence of yesterday, tomorrow will be a consequence of today in exactly the same way. And if one has studied thoroughly what happened yesterday, the day before yesterday, a week ago, a year, ten years ago, one can say unmistakably what will and what will not happen tomorrow. But at present we have not sufficient material at our disposal to discuss this question seriously. What happens or may happen to us may depend upon three causes: upon accident, upon fate, or upon our own will. Such as we are, we are almost wholly dependent upon accident. We can have no fate in the real sense of the word any more than we can have will. If we had will, then through this alone we

101

should know the future, because we should then make our future, and make it such as we want it to be. If we had fate, we could also know the future, because fate corresponds to type. If the type is known, then its fate can be known, that is, both the past and the future. But accidents cannot be foreseen. Today a man is one, tomorrow he is different: today one thing happens to him, tomorrow another.”

“But are you not able to foresee what is going to happen to each of us,” somebody asked, “that is to say, foretell what result each of us will reach in work on himself and whether it is worth his while to begin work?”

“It is impossible to say,” said G. “One can only foretell the future for men. It is impossible to foretell the future for mad machines. Their direction changes every moment. At one moment a machine of this kind is going in one direction and you can calculate where it can get to, but five minutes later it is already going in quite a different direction and all your calculations prove to be wrong. Therefore, before talking about knowing the future, one must know whose future is meant. If a man wants to know his own future he must first of all know himself. Then he will see whether it is worth his while to know the future. Sometimes, maybe, it is better not to know it.

“It sounds paradoxical but we have every right to say that we know our future. It will be exactly the same as our past has been. Nothing can change of itself.

“And in practice, in order to study the future one must learn to notice and to remember the moments when we really know the future and when we act in accordance with this knowledge. Then judging by results, it will be possible to demonstrate that we really do know the future. This happens in a simple way in business, for instance. Every good commercial businessman knows the future. If he does not know the future his business goes smash. In work on oneself one must be a good businessman, a good merchant. And knowing the future is worth while only when a man can be his own master.

“There was a question here about the future life, about how to create it, how to avoid final death, how not to die.

“For this it is necessary ‘to be’ If a man is changing every minute, if there is nothing in him that can withstand external influences, it means that there is nothing in him that can withstand death. But if he becomes independent of external influences, if there appears in him something that can live by itself, this something may not die. In ordinary circumstances we die every moment. External influences change and we change with them, that is, many of our I’s die. If a man develops in himself a permanent I that can survive a change in external conditions, it can survive the death of the physical body. The whole secret is that one cannot work for a future life without working for this one. In working for life a man works for death, or rather, for immortality. Therefore work for immortality,

102

if one may so call it, cannot be separated from general work. In attaining the one, a man attains the other. A man may strive to be simply for the sake of his own life’s interests. Through this alone he may become immortal. We do not speak specially of a future life and we do not study whether it exists or not, because the laws are everywhere the same. In studying his own life as he knows it, and the lives of other men, from birth to death, a man is studying all the laws which govern life and death and immortality. If he becomes the master of his life, he may become the master of his death.

“Another question was how to become a Christian.

“First of all it is necessary to understand that a Christian is not a man who calls himself a Christian or whom others call a Christian. A Christian is one who lives in accordance with Christ’s precepts. Such as we are we cannot be Christians. In order to be Christians we must be able ‘to do.’ We cannot do; with us everything ‘happens.’ Christ says: ‘Love your enemies,’ but how can we love our enemies when we cannot even love our friends? Sometimes ‘it loves’ and sometimes ‘it does not love.’ Such as we are we cannot even really desire to be Christians because, again, sometimes ‘it desires’ and sometimes ‘it does not desire.’ And one and the same thing cannot be desired for long, because suddenly, instead of desiring to be a Christian, a man remembers a very good but very expensive carpet that he has seen in a shop. And instead of wishing to be a Christian he begins to think how he can manage to buy this carpet, forgetting all about Christianity. Or if somebody else does not believe what a wonderful Christian he is, he will be ready to eat him alive or to roast him on hot coals. In order to be a good Christian one must be. To be means to be master of oneself. If a man is not his own master he has nothing and can have nothing. And he cannot be a Christian. He is simply a machine, an automaton. A machine cannot be a Christian. Think for yourselves, is it possible for a motorcar or a typewriter or a gramophone to be Christian? They are simply things which are controlled by chance. They are not responsible. They are machines. To be a Christian means to be responsible. Responsibility comes later when a man even partially ceases to be a machine, and begins in fact, and not only in words, to desire to be a Christian.”

“What is the relation of the teaching you are expounding to Christianity as we know it?” asked somebody present.

“I do not know what you know about Christianity,” answered G., emphasizing this word. “It would be necessary to talk a great deal and to talk for a long time in order to make clear what you understand by this term. But for the benefit of those who know already, I will say that, if you like, this is esoteric Christianity. We will talk in due course about the meaning of these words. At present we will continue to discuss our questions.

103

“Of the desires expressed the one which is most right is the desire to be master of oneself, because without this nothing else is possible. And in comparison with this desire all other desires are simply childish dreams, desires of which a man could make no use even if they were granted to him.

“It was said, for instance, that somebody wanted to help people. In order to be able to help people one must first learn to help oneself. A great number of people become absorbed in thoughts and feelings about helping others simply out of laziness. They are too lazy to work on themselves; and at the same time it is very pleasant for them to think that they are able to help others. This is being false and insincere with oneself. If a man looks at himself as he really is, he will not begin to think of helping other people: he will be ashamed to think about it. Love of mankind, altruism, are all very fine words, but they only have meaning when a man is able, of his own choice and of his own decision, to love or not to love, to be an altruist or an egoist. Then his choice has a value. But if there is no choice at all, if he cannot be different, if he is only such as chance has made or is making him, an altruist today, an egoist tomorrow, again an altruist the day after tomorrow, then there is no value in it whatever. In order to help others one must first learn to be an egoist, a conscious egoist. Only a conscious egoist can help people. Such as we are we can do nothing. A man decides to be an egoist but gives away his last shirt instead. He decides to give away his last shirt, but instead, he strips of his last shirt the man to whom he meant to give his own. Or he decides to give away his own shirt but gives away somebody else’s and is offended if somebody refuses to give him his shirt so that he may give it to another. This is what happens most often. And so it goes on.

“And above all, in order to do what is difficult, one must first learn to do what is easy. One cannot begin with the most difficult.

“There was a question about war. How to stop wars? Wars cannot be stopped. War is the result of the slavery in which men live. Strictly speaking men are not to blame for war. War is due to cosmic forces, to planetary influences. But in men there is no resistance whatever against these influences, and there cannot be any, because men are slaves. If they were men and were capable of ‘doing,’ they would be able to resist these influences and refrain from killing one another.”

“But surely those who realize this can do something?” said the man who had asked the question about war. “If a sufficient number of men came to a definite conclusion that there should be no war, could they not influence others?”

“Those who dislike war have been trying to do so almost since the creation of the world,” said G. “And yet there has never been such a war as the present. Wars are not decreasing, they are increasing and war cannot be stopped by ordinary means. All these theories about universal peace,

104

about peace conferences, and so on, are again simply laziness and hypocrisy. Men do not want to think about themselves, do not want to work on themselves, but think of how to make other people do what they want. If a sufficient number of people who wanted to stop war really did gather together they would first of all begin by making war upon those who disagreed with them. And it is still more certain that they would make war on people who also want to stop wars but in another way. And so they would fight. Men are what they are and they cannot be different. War has many causes that are unknown to us. Some causes are in men themselves, others are outside them. One must begin with the causes that are in man himself. How can he be independent of the external influences of great cosmic forces when he is the slave of everything that surrounds him? He is controlled by everything around him. If he becomes free from things, he may then become free from planetary influences.

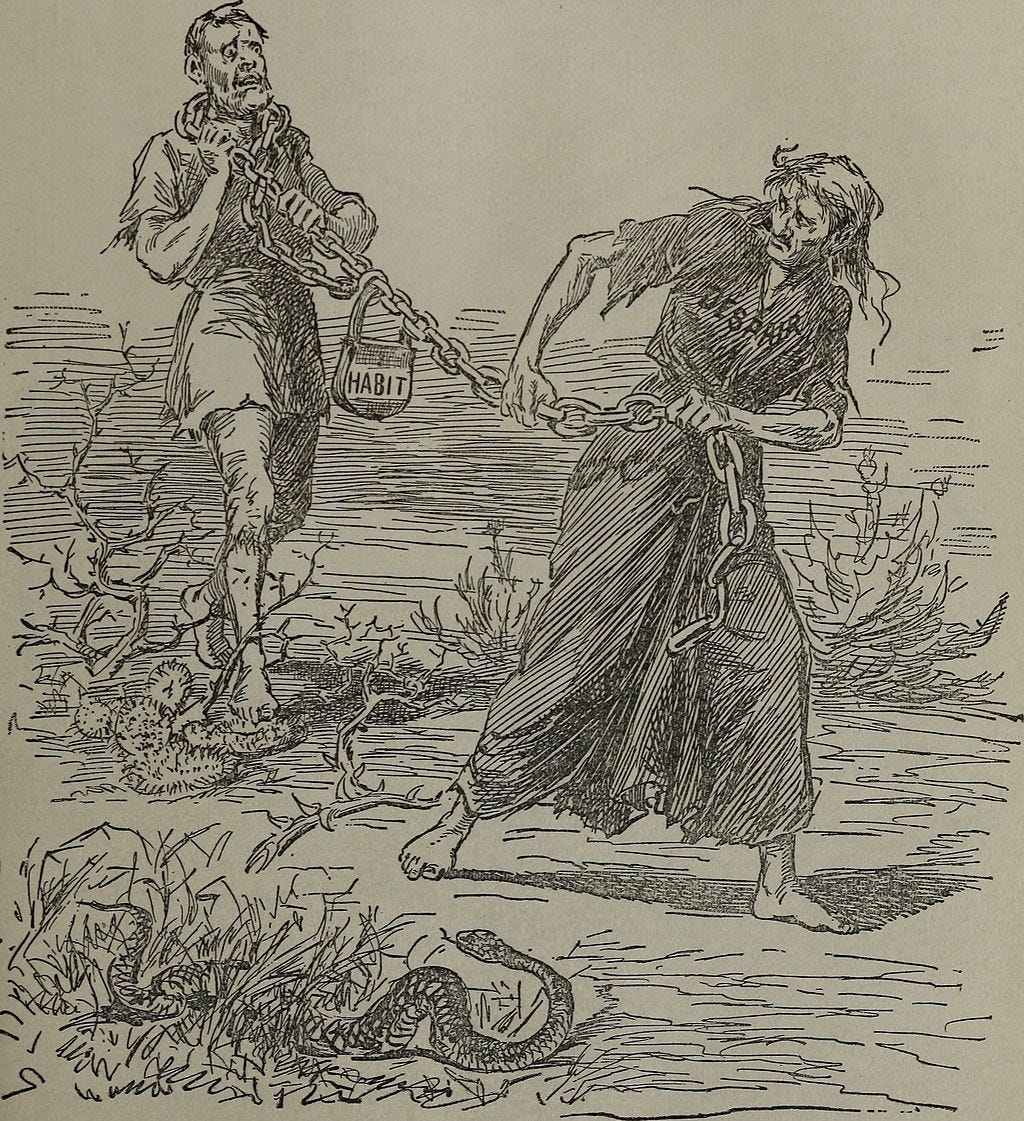

“Freedom, liberation, this must be the aim of man. To become free, to be liberated from slavery: this is what a man ought to strive for when he becomes even a little conscious of his position. There is nothing else for him, and nothing else is possible so long as he remains a slave both inwardly and outwardly. But he cannot cease to be a slave outwardly while he remains a slave inwardly. Therefore in order to become free, man must gain inner freedom.

“The first reason for man’s inner slavery is his ignorance, and above all, his ignorance of himself. Without self-knowledge, without understanding the working and functions of his machine, man cannot be free, he cannot govern himself and he will always remain a slave, and the plaything of the forces acting upon him.

“This is why in all ancient teachings the first demand at the beginning of the way to liberation was: ‘Know thyself.’

“We shall speak of these words now.”