This is the twenty third of our weekly readings in Fragments Reading Club from P.D. Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous, where we are gradually working our way through the whole book. Please post comments and questions.

See this link for the beginning of the book.

(If you are a subscriber to The Journal of Gurdjieff Studies, you can opt in or out of receiving emails from the Fragments Reading Club category.)

Further experiences. Sleep in a waking state and awakening. What European psychology has overlooked. Differences in the understanding of the idea of consciousness. The study of man is parallel to the study of the world. Following upon the law of three comes the fundamental law of the universe: The law of seven or the law of octaves. The absence of continuity in vibrations. Octaves.

Sometimes self-remembering was not successful; at other times it was accompanied by curious observations.

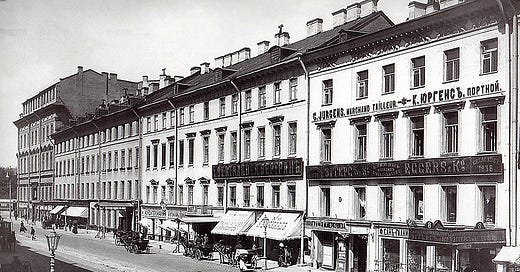

I was once walking along the Liteiny towards the Nevsky, and in spite of all my efforts I was unable to keep my attention on self-remembering. The noise, movement, everything distracted me. Every minute I lost the thread of attention, found it again, and then lost it again. At last I felt a kind of ridiculous irritation with myself and I turned into the street on the left having firmly decided to keep my attention on the fact that I would remember myself at least for some time, at any rate until I reached the following street. I reached the Nadejdinskaya without losing the thread of attention except, perhaps, for short moments. Then I again turned towards the Nevsky realizing that, in quiet streets, it was easier for me not to lose the line of thought and wishing therefore to test myself in more noisy streets. I reached the Nevsky still remembering myself, and was already beginning to experience the strange emotional state of inner peace and confidence which comes after great efforts of this kind. Just round the corner on the Nevsky was a tobacconist's shop where they made my cigarettes. Still remembering myself I thought I would call there and order some cigarettes.

Two hours later I woke up in the Tavricheskaya, that is, far away. I was going by izvostchik to the printers. The sensation of awakening was extraordinarily vivid. I can almost say that I came to. I remembered everything at once. How I had been walking along the Nadejdinskaya, how I had been remembering myself, how I had thought about cigarettes, and how at this thought I seemed all at once to fall and disappear into a deep sleep.

At the same time, while immersed in this sleep, I had continued to perform consistent and expedient actions. I left the tobacconist, called at my flat in the Liteiny, telephoned to the printers. I wrote two letters.

121

Then again I went out of the house. I walked on the left side of the Nevsky up to the Gostinoy Dvor intending to go to the Ofitzerskaya. Then I had changed my mind as it was getting late. I had taken an izvostchik and was driving to the Kavalergardskaya to my printers. And on the way while driving along the Tavricheskaya I began to feel a strange uneasiness, as though I had forgotten something.—And suddenly I remembered that I had forgotten to remember myself.

I spoke of my observations and deductions to the people in our group as well as to my various literary friends and others.

I told them that this was the center of gravity of the whole system and of all work on oneself; that now work on oneself was not only empty words but a real fact full of significance thanks to which psychology becomes an exact and at the same time a practical science.

I said that European and Western psychology in general had overlooked a fact of tremendous importance, namely, that we do not remember ourselves; that we live and act and reason in deep sleep, not metaphorically but in absolute reality. And also that, at the same time, we can remember ourselves if we make sufficient efforts, that we can awaken.

I was struck by the difference between the understanding of the people who belonged to our groups and that of people outside them. The people who belonged to our groups understood, though not all at once, that we had come into contact with a "miracle," and that it was something "new," something that had never existed anywhere before.

The other people did not understand this; they took it all too lightly and sometimes they even began to prove to me that such theories had existed before.

A. L. Volinsky, whom I had often met and with whom I had talked a great deal since 1909 and whose opinions I valued very much, did not find in the idea of "self-remembering" anything that he had not known before.

"This is an apperception." He said to me, "Have you read Wundt's Logic? You will find there his latest definition of apperception. It is exactly the same thing you speak of. 'Simple observation' is perception. 'Observation with self-remembering,' as you call it, is apperception. Of course Wundt knew of it."

I did not want to argue with Volinsky. I had read Wundt. And of course what Wundt had written was not at all what I had said to Volinsky. Wundt had come close to this idea, but others had come just as close and had afterwards gone off in a different direction. He had not seen the magnitude of the idea which was hidden behind his thoughts about different forms of perception. And not having seen the magnitude

122

of the idea he of course could not see the central position which the idea of the absence of consciousness and the idea of the possibility of the voluntary creation of this consciousness ought to occupy in our thinking. Only it seemed strange to me that Volinsky could not see this even when I pointed it out to him.

I subsequently became convinced that this idea was hidden by an impenetrable veil for many otherwise very intelligent people—and still later on I saw why this was so.

The next time G. came from Moscow he found us immersed in experiments in self-remembering and in discussions about these experiments. But at his first lecture he spoke of something else.

"In right knowledge the study of man must proceed on parallel lines with the study of the world, and the study of the world must run parallel with the study of man. Laws are everywhere the same, in the world as well as in man. Having mastered the principles of any one law we must look for its manifestation in the world and in man simultaneously. Moreover, some laws are more easily observed in the world, others are more easily observed in man. Therefore in certain cases it is better to begin with the world and then to pass on to man, and in other cases it is better to begin with man and then to pass on to the world.

"This parallel study of the world and of man shows the student the fundamental unity of everything and helps him to find analogies in phenomena of different orders.

"The number of fundamental laws which govern all processes both in the world and in man is very small. Different numerical combinations of a few elementary forces create all the seeming variety of phenomena.

"In order to understand the mechanics of the universe it is necessary to resolve complex phenomena into these elementary forces.

"The first fundamental law of the universe is the law of three forces, or three principles, or, as it is often called, the law of three. According to this law every action, every phenomenon in all worlds without exception, is the result of a simultaneous action of three forces—the positive, the negative, and the neutralizing. Of this we have already spoken, and in future we will return to this law with every new line of study.

"The next fundamental law of the universe is the law of seven or the law of octaves.

"In order to understand the meaning of this law it is necessary to regard the universe as consisting of vibrations. These vibrations proceed in all kinds, aspects, and densities of the matter which constitutes the universe, from the finest to the coarsest; they issue from various sources and proceed in various directions, crossing one another, colliding, strengthening, weakening, arresting one another, and so on.

123

"In this connection according to the usual views accepted in the West, vibrations are continuous. This means that vibrations are usually regarded as proceeding uninterruptedly, ascending or descending so long as there continues to act the force of the original impulse which caused the vibration and which overcomes the resistance of the medium in which the vibrations proceed. When the force of the impulse becomes exhausted and the resistance of the medium gains the upper hand the vibrations naturally die down and stop. But until this moment is reached, that is, until the beginning of the natural weakening, the vibrations develop uniformly and gradually, and, in the absence of resistance, can even be endless. So that one of the fundamental propositions of our physics is the continuity of vibrations, although this has never been precisely formulated because it has never been opposed. In certain of the newest theories this proposition is beginning to be shaken. Nevertheless physics is still very far from a correct view on the nature of vibrations, or what corresponds to our conception of vibrations, in the real world.

"In this instance the view of ancient knowledge is opposed to that of contemporary science because at the base of the understanding of vibrations ancient knowledge places the principle of the discontinuity of vibrations.

"The principle of the discontinuity of vibration means the definite and necessary characteristic of all vibrations in nature, whether ascending or descending, to develop not uniformly but with periodical accelerations and retardations. This principle can be formulated still more precisely if we say that the force of the original impulse in vibrations does not act uniformly but, as it were, becomes alternately stronger and weaker. The force of the impulse acts without changing its nature and vibrations develop in a regular way only for a certain time which is determined by the nature of the impulse, the medium, the conditions, and so forth. But at a certain moment a kind of change takes place in it and the vibrations, so to speak, cease to obey it and for a short time they slow down and to a certain extent change their nature or direction; for example, ascending vibrations at a certain moment begin to ascend more slowly, and descending vibrations begin to descend more slowly. After this temporary retardation, both in ascending and descending, the vibrations again enter the former channel and for a certain time ascend or descend uniformly up to a certain moment when a check in their development again takes place. In this connection it is significant that the periods of uniform action of the momentum are not equal and that the moments of retardation of the vibrations are not symmetrical. One period is shorter, the other is longer.

"In order to determine these moments of retardation, or rather, the checks in the ascent and descent of vibrations, the lines of development of

124

vibrations are divided into periods corresponding to the doubling or the halving of the number of vibrations in a given space of time.

"Let us imagine a line of increasing vibrations. Let us take them at the moment when they are vibrating at the rate of one thousand a second. After a certain time the number of vibrations is doubled, that is, reaches two thousand.

"It has been found and established that in this interval of vibrations, between the given number of vibrations and a number twice as large, there are two places where a retardation in the increase of vibrations takes place. One is near the beginning but not at the beginning itself. The other occurs almost at the end.

"Approximately:

"The laws which govern the retardation or the deflection of vibrations from their primary direction were known to ancient science. These laws were duly incorporated into a particular formula or diagram which has been preserved up to our times. In this formula the period in which vibrations are doubled was divided into eight unequal steps corresponding to the rate of increase in the vibrations. The eighth step repeats the first step with double the number of vibrations. This period of the doubling of the vibrations, or the line of the development of vibrations, between a given number of vibrations and double that number, is called an octave, that is to say, composed of eight.

"The principle of dividing into eight unequal parts the period, in which the vibrations are doubled, is based upon the observation of the non-uniform increase of vibrations in the entire octave, and separate 'steps' of the octave show acceleration and retardation at different moments of its development.

"In the guise of this formula ideas of the octave have been handed down from teacher to pupil, from one school to another. In very remote times one of these schools found that it was possible to apply this formula to music. In this way was obtained the seven-tone musical scale which was known in the most distant antiquity, then forgotten, and then discovered or 'found' again.