(6.) - Maurice Nicoll 1 - Commentary II - On ADDITIONAL MEANS OF SELF-OBSERVATION, pp.19-25

This is number 6.) of our sequential postings from Volume 1 of Maurice Nicoll’s Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky.

(If you are a subscriber to The Journal of Gurdjieff Studies, you can opt in or out of receiving emails from the Fragments Reading Club category.)

Links to each commentary will be put on the following Contents page, as we progress through the book:

COMMENTARY II - Birdlip, June 6, 1941

ON ADDITIONAL MEANS OF SELF-OBSERVATION

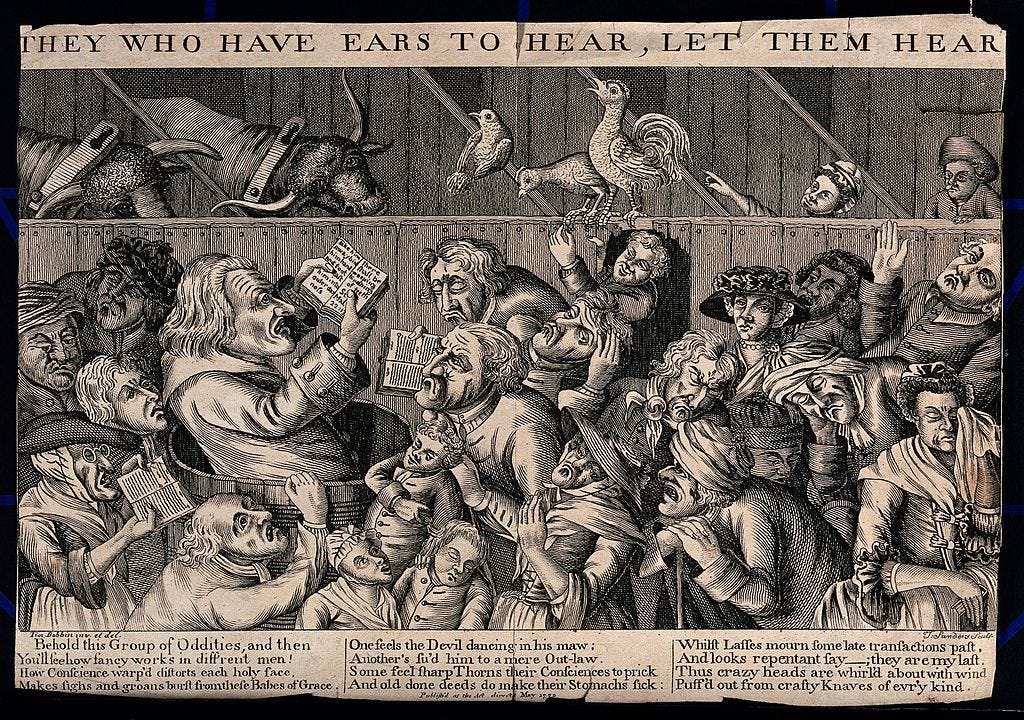

Section I—The following is a commentary, which refers to the idea of different 'I's in us. As you know, in this system of teaching, man is not regarded as a unity. The lack of unity in a man is the source of all his difficulties and troubles. Man's body is a unity and works as an organized whole unless it is sick. But man's inner life is not a unity and has not organization and does not work harmoniously as a whole. Man, in regard to his inner state, is a multiplicity, and from one angle in this teaching, this inner multiplicity is spoken of in terms of ‘I’s or egos in a man. Man has no one permanent ‘I’ but a host of different ‘I’s in him that at each moment take charge of him and speak out of him as if in his voice: and from this point of view man is compared with a house in disorder in which there is no master but a crowd of servants who speak in the name of the absent master. As you have

20

probably all heard, it is the greatest mistake that can be made either to suppose that oneself or others have one permanent unchanging ‘I’ —or ego—in them. A man is never the same for long. He is continually changing. But he imagines that if a person is called James he is always James. This is quite untrue. This man whom we call James has in him other ‘I’s, other egos, which take charge of him at different moments, and although perhaps James does not like telling lies, another ‘I’ in him—let us call it Peter—likes to lie and so on. To take another person as one and the same person at all times, to suppose he is one single ‘I’, is to do violence to him and in the same way is to do violence to oneself. A multitude of different people live in each of you. These are all the different ‘I’s belonging to personality, which it is necessary to observe, and try to get to know, otherwise no self-knowledge is possible—that is, if one really seeks self-knowledge and not invention and imagination about oneself. Not one of you here has a real permanent, unchanging ‘I’. Not one of you here has real unity of being. All of you are nothing but a crowd of different people, some better and some worse, and each of these people—each of these ‘I’s in you—at particular moments takes charge of you and makes you do what it wants and say what it wishes and feel and think as it feels and thinks. But you already know all this and I want to speak in more detail about this doctrine of many ‘I’s in a man and suggest to you something about its deeper meaning and significance. If some of you cannot understand what follows, it is either because you have not yet had sufficient practice in self-observation, in which case you must be patient and wait a little, or it is because, if you have been longer in the work, you have not even begun seriously to observe yourselves yet—that is, you have not begun to work on yourselves and perhaps even have never seriously thought what it means. In the latter case, I can only say that you must really try to make an effort to understand what it means, through actual self-observation, and as soon as possible, for time is counted in the work, and opportunities begin of themselves to get fewer and if one does not take them while it is possible it may, in the very nature of things, become too late to do anything with oneself in the way of inner change, which is only possible through self-observation and the self-knowledge that comes from it.

The first point to which I will draw your attention in connection with the doctrine of many ‘I’s in a man is that as long as a man takes himself as one he cannot change. But have you thought for yourselves—that is, from your own private thinking—why this is so? You all know that this work is to make a man think for himself and that to hear the ideas of this system without thinking about them for oneself and so making them become part of oneself is so much waste of time. The work is not something external, but internal, and people who imagine that the work, as an external organization, will carry them along are sadly mistaken about its meaning. The very fact that the work begins with self-observation surely is sufficient to shew that it demands a

21

personal effort on the part of each Individual and only each of you can observe himself or herself and no one else can do this for you. Now it is only through the effort of self-observation that a man can eventually see for himself that he is not one and so break the illusion that he is one permanent unvarying individual. For as long as a man has this illusion that he is always one and the same person, he cannot change —and, as you know, the object of this work is to bring about a gradual change in one's inner life. In fact, the whole of this work is based on the idea that self-change or transformation of oneself is a definite possibility in everyone and is the real goal of existence. But the starting-point of this self-change remains hidden as long as a man is under the illusion that he is one. A man must realize for himself that he is not one but many and he can only do this by means of uncritical observation of himself. But for a long time the illusion that he is always one and the same person will struggle with his attempt to observe himself uncritically and make it difficult for him to realize the significance of his observations. He will find excuses and justify himself and so cling to the idea that he is really one and has a permanent individuality and that he always knows what he is doing and thinking and saying and is always conscious of himself and in control of himself at all times. It will be very difficult for him to admit to himself that this is not the case. And on the other hand, it will be quite useless if he pretends to believe that he is not one and does not see the truth of it for himself. It is a part of the knowledge of this system of teaching that man is not one but many. But merely as knowledge it lies only in a man's memory. Unless a man sees the truth of this knowledge by applying it to himself, by working on his being, it cannot become understanding. A man may say: "I know I am not one but many—the work says so." But that is nothing. The knowledge remains external to the man himself. But if he applies this knowledge practically and through long self-observation begins to see the truth of it, then he will say: "I understand I am not one but many"—and this is quite a different thing. The knowledge will have borne fruit in him, so to speak, and will no longer be merely knowledge, but understanding, because the man has applied the knowledge to himself and by means of it worked on his own being. And you will remember the great emphasis laid in this system on the difference between knowledge and understanding and how often it is said that in these times to-day knowledge has gone far beyond understanding, because man has developed only on the side of knowledge and not correspondingly on the side of being.

When a man begins to observe himself from the angle that he is not one but many, he begins to work on his being. He cannot do this if he remains under the conviction that he is one, for then he will not be able to separate himself from himself, for he will take everything in him, every thought, mood, feeling, impulse, desire, emotion, and so on, as himself—that is, as 'I'. But if he begins to observe himself, he will then, at that moment, become two—an observing side and an observed side.

22

And unless he divides himself in this way and struggles to make this division more and more distinct, he will never be able to shift from where he is, because, always taking everything that takes place in him as himself, he will say to it all and so everything will then be 'I' in him, and by identifying himself with everything that happens in himself, and taking it all as ‘I’, he will make it impossible to change everything, for everything will hide itself behind this illusion of 'I' and continue to live in him. In fact, the whole crowd of people in a man—the crowd of separate ‘I’s in him—both the useful and useless—will have, as it were, equal rights and be equally protected by him because he will be quite unable to distinguish them from one another since he takes them all as himself. This is merely one way of putting the situation within a man who remains convinced that he is one. Now a man cannot begin to change until he is able as the result of self-observation to say: "This is not I". As soon as he can begin to say this internally to something he observes in himself, he begins to separate it from himself. That is, he begins to take the feeling of ‘I’ out of it and the result is, eventually, and often only after a struggle, that what he has observed begins to move away from him and so pass, as it were, into the distance in his inner world. But this is impossible if he thinks that what he has observed is himself, for then it will still be ‘I’ in him and 'I' cannot change ‘I’, for then no separation will be possible and he will remain united with what he has observed, by taking it as ‘I’—that is, as himself—instead of taking it as an ‘I’ in him.

When a man is thinking he believes that it is himself thinking. But our thoughts come at random, unless we are thinking deeply and with attention, which is very rare. The thoughts that pass across our minds come from different ‘I’s in us. Let us suppose a man notices that he is having negative thoughts about the work or about a person or something that has happened. Let us suppose that he takes these thoughts as his own—as himself—that is, as ‘I’—and let us also suppose that he feels some discomfort about them. He says to himself: "I must really not think in this way." This may have some result or it may not. But the point is that he is making a mistake—namely, the mistake of taking all that happens within him as himself, as ‘I’. If he observes himself rightly, he notices these thoughts not as himself but as coming from a negative ‘I’ in him, which perhaps he knows something about already. Let us suppose he knows this ‘I’ in him fairly well. He recognizes at once that this ‘I’ is talking in him and communicating its thoughts to him through the mental centre and stirring up at the same time a particular kind of negative emotion. He does not for a moment take this negative ‘I’ as himself but sees it as something in him apart from himself. As a result what it says does not get power over him, because he is separate from it. But if he goes to sleep in himself—that is, if he ceases to be conscious of what is going on in him and which ‘I’s are close to him—he falls under its power and, becoming identified with it, imagines that it is he himself who is thinking in that way. By doing

23

this, he strengthens the power of this negative ‘I’ over him—because, as you know, whatever we identify with at once has power over us, and the more often we identify with something, the more we are slaves to it. In regard to the work itself, our temptations lie exactly in negative ‘I’s—that is, in ‘I’s that hate the work because their lives in us are threatened by it. These negative ‘I’s start certain kinds of thoughts through acting on the mental centre and using the material stored there in the form of rolls. If we go with these thoughts—that is, with these negative ‘I’s that are at the moment working in us—we are unable to shake off their effect. Their first effect is to make us feel a loss of force. Whenever we feel a sudden loss of force, it is practically always due to the action of a negative ‘I’ which has started a train of thought from our memories and, by carefully selecting its material, represented something in a wrong light—and it must be remembered that all negative ‘I’s can only lie, just as all negative emotions can only distort everything, as, for instance, the emotion of suspicion. Unless we can observe the action of the negative ‘I’ in the mental centre, it will gain power over us. It will gain power instantly if we take it as ‘I’—as ourselves. But if we see it as an ‘I’ at work in us, it cannot do so. But in order to realize that it is an ‘I’ in us, we must already have become certain, by practical work on ourselves, that many different ‘I’s exist in us, and that we are not one, but many.

***

Section II—Let us return to the illusion everyone has that he is one. This illusion exists in each of you. It can only be discovered gradually by personal observation. Each of you ascribes to himself the possession of individuality and not only individuality but full consciousness and will. But as you know this system of ideas that we are studying teaches that man is not one, but many—that is, he is not one individual, but many different people—and also that he is not properly conscious but nearly always asleep in dreams, in imagination, in considering, in negative emotions, and so on, and as a result does not remember himself and so, as it were, wastes and destroys his inner life, and lives in a sort of darkness and finally that he does not possess will but has many different wills which conflict with one another and act in different directions. If man were a unity instead of being a multiplicity, he would have true individuality. He would be one and so would have one will. The illusion, therefore, that a man has about himself that he is one refers to a possibility. Man can attain unity of being. He can reach his true individuality. But it is precisely this illusion that stands first of all in the way of man's attainment of this possibility. For as long as a man imagines he has something, he will not seek for it. Why should a man strive for something that he has never doubted for a moment that he possesses already? This is one of the effects of the imagination, which fills up, as it were, what is lacking or makes it appear that we are like this, or like that, when actually we are the reverse. In this work it is

24

constantly said that we must struggle with imagination and you must understand that this refers also to imagination about ourselves. It is necessary to struggle with our imagination about ourselves, not only because it puts us into false experiences, artificial emotions and often ridiculous situations, but because it stops all possibility of inner growth. And it is easy now to see why this is so from what has been said already. For if we imagine that we have already got qualities of being that we are far from possessing, we can never expect to have them. Our imagination will supply the deficiency. In fact, we will never know that we lack anything in regard to ourselves—that is, in regard to the quality of our being—and will think that the only things that we lack are appreciation, fame, money, opportunity or some other external thing, but that in regard to ourselves nothing is seriously lacking. This is the power that illusion has and for this reason it is said, in the work-parable of the sheep and the magicians, that man is hypnotized through his imagination and is under the illusion that he is a lion or an eagle when he is really a sheep; and at the same time, as a sheep he has the power of escaping from the magicians, who are too lazy or too mean to build fences to shut him in.

What we have to understand from all this is that an illusion is something very real and definite in its effects. The imagination is not merely nothing—"nothing but imagination", as we say. It is something very powerful indeed. It is an actual force acting universally on mankind and keeping man in a state of sleep, whether he be primitive or civilized. And until a man begins to know what it is to remember himself—that is, to reach up to the third state of consciousness—the force that manifests itself as imagination in the two lower states of consciousness does not find its right direction and so acts against him. As we have seen, man imagines he is one and because of this illusion he cannot shift from where he is in himself. Everyone is, in himself, at a certain stage of himself, and no one can shift from this stage where he is in himself unless he sees very distinctly for himself that he is not one and the same person, but many different people and that to continue to think he is one is an illusion.

This realization, this inner perception, changes a person's feeling of himself. It changes, or begins to change, his feeling of 'I'. As long as he lives in the illusion that he is one, he has a wrong feeling of 'I'. But he does not know this: nor does he know that because of it not only is his life all wrong, and his intercourse with others all wrong, but his own evolution is made impossible. For a man cannot change as long as he ascribes to himself oneness of being, for then everything in him is himself. He will ascribe to himself everything good or bad in himself. He will be responsible for every thought and for every mood, through taking everything in himself as himself, because if he believes that everything he thinks and does and says, he thinks and does and says from himself, then it will be his own because he makes it all his own by ascribing it all to himself. The illusion that he is always one and the

25

same person and that he is fully conscious of everything, and that he has will and so is in control of himself, will totally blind him to the fact that he is not the conscious origin of all that he thinks and says and does. Self-observation will shew him that he has practically no control of his thoughts and cannot even stop thinking if he tries to do so and that thoughts of every kind come and go in his mind whether he wishes them or not. And it is the same with his feelings and with his moods, and his words and his actions. But if he cannot admit that he is other than fully conscious of all he says and does and in full control of his thoughts and moods and feelings and always one and the same person, all this will remain hidden, concealed from him by the power of his own imagination, and the whole sense of himself, his whole sense of 'I', and his relationship to his inner states, will be false. But if a man, through practical and sincere self-observation, no longer believes that he is one and no longer ascribes to this imagined one person all that exists and all that enters in his inner world, he begins to make it possible for him to change. For a man can receive help only through what he believes. If he believes he is one, help cannot reach him, for he ascribes everything to himself and so is not only guilty of everything, but is, as it were, filled entirely with himself, and there is no room for anything else. But when a man sees that he has no right to think of himself as one and that very many different people and some very unpleasant ones exist in him and that he is by no means fully conscious and certainly has no individual will, although this goes against his vanity and is painful to his pride, it is the starting-point of change of being.