This is a continuation of a series of articles on The Prolongation of Life.

A reminder to readers that these posts often assume background knowledge of the literature (see Bibliography). Members' articles especially assume good familiarity with Gurdjieff's All and Everything and secondary material. For this series of posts on The Prolongation of Life, having read at least Views from the Real World and In Search of the Miraculous, and, ideally, Beelzebub's Tales to his Grandson, is recommended. For a basic bibliography and links to books, see Introduction and Further Bibliography.

For sources of quotes etc, see Economising Experiences - Members' post with references.

At the end of the previous article in this series, The Prolongation of Life - Sacrificing Suffering, Thomas de Hartmann was quoted, where, among other things, he spoke of attention as something that could prolong life. Related to this is another striking, and difficult to understand, statement - one of the Study House aphorisms at the Prieuré, though its meaning is enlarged upon, for example, in Gurdjieff's first series [1] and some of his talks [2]:

37. Man is given a definite number of experiences—economizing them, he prolongs his life [3].

Why would economising experiences prolong life? First of all, what is an experience, as Gurdjieff means the word? In a talk in New York, February 1924, as recorded in Views from the Real World, he says:

Man is born, it is said, with a mechanism adapted for receiving many kinds of impressions. The perception of some of these impressions begins before birth; and during his growth more and more receiving apparatuses spring forth and become perfected.

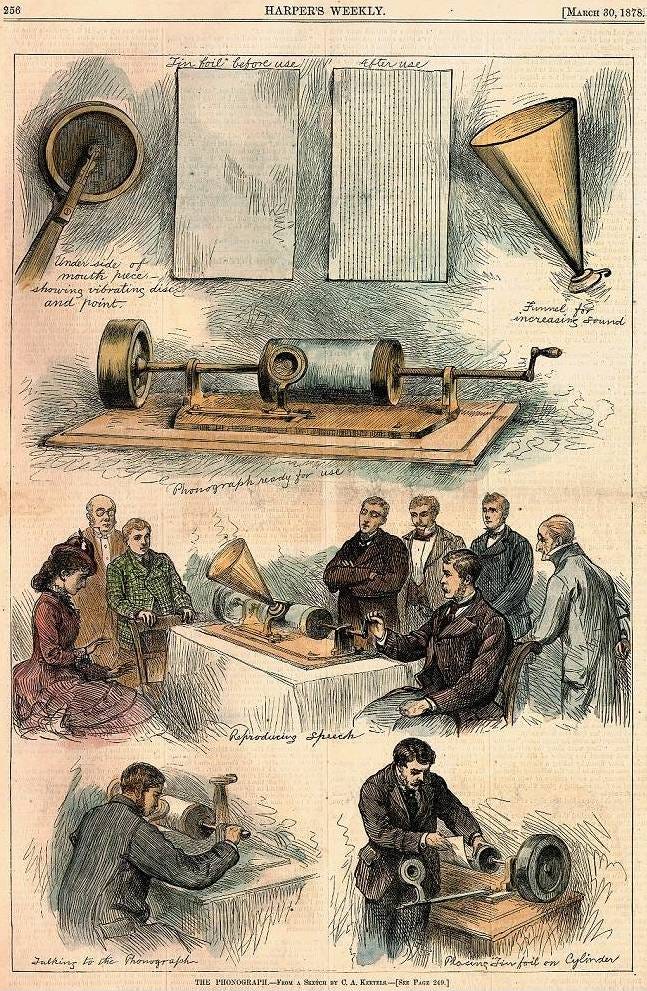

The construction of these receiving apparatuses is the same, recalling the clean wax discs from which phonograph records are made. On these rolls and reels all the impressions received are noted down, from the first day of life and even before. Besides this, the mechanism has one more automatically acting adjustment, thanks to which all newly received impressions are connected with those previously recorded.

In addition to these a chronological record is kept. Thus every impression which has been experienced is written down in several places on several rolls. On these rolls it is preserved unchanged. What we call memory is a very imperfect adaptation by means of which we can keep on record only a small part of our store of impressions; but impressions once experienced never disappear; they are preserved on rolls where they are written down… [4]

It is as if experiences, in Gurdjieff's terminology, which in the first quotation he says are given, are about the possibility of receiving new impressions, or the "space" on the "rolls and reels." He gives warnings in various places about the limited time available for this [5]. He speaks in the first series of All and Everything of "the possibilities for experiencing put into them by Nature [6]," and the definite duration for the unwinding of the spring-like Bobbin-kandelnost in each brain, as determined by the "seven exterior actualizations" of the principle of Itoklanoz [7].

Thus, one meaning of "prolongation of life," in Gurdjieff's exposition, seems to be related to the capacity to receive new impressions, to record new experiences. And as "the perfection of a being depends on the quality and quantity of his inner experiencings," [8] the prolongation and intensification of this capacity during one's life has great significance for inner development. The other side of this is premature "unwinding" of the rolls, for example, the description in Gurdjieff's first series of death by thirds [9], or In Search of the Miraculous of meeting dead people:

"Moreover, it happens fairly often that essence dies in a man while his personality and his body are still alive. A considerable percentage of the people we meet in the streets of a great town are people who are empty inside, that is, they are actually already dead [10].

Going back to the meaning of the word experiences in Gurdjieff's usage, Orage said:

"Experiences are physiological processes taking place in us of which, at the time, we are usually unaware - we remember them afterwards [11]."

The words, "at the time, we are usually unaware," also bring to mind the moment of the reception of a new impression. It is this moment that is usually missed, because the "excellently working automatism" takes care of things, and we have "no need of making any individual effort whatsoever [12]." Thus we lose our birthright of remembering ourselves. How are we to reclaim this?

Continued in Proving the Moment [Members' Article]