This is the thirty-second of our weekly readings in Fragments Reading Club from P.D. Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous, where we are gradually working our way through the whole book. Please post comments and questions.

See this link for the beginning of the book.

The Current list of posts in Fragments Reading Club is updated regularly, for handy navigation.

(If you are a subscriber to The Journal of Gurdjieff Studies, you can opt in or out of receiving emails from the Fragments Reading Club category.)

Matter in the light of its chemical, physical, psychic and cosmic properties. Intelligence of matter. "Atom." Every human function and state depends on energy. Substances in man. Man has sufficient energy to begin work on himself, if he saves his energy. Wastage of energy.

"All matters from 'hydrogen' 6 to 'hydrogen' 3072 are to be found and play a part in the human organism. Each of these 'hydrogens' includes a very large group of chemical substances known to us, linked together by some function in connection with our organism. In other words, it must not be forgotten that the term 'hydrogen' has a very wide meaning. Any

175

simple element is a 'hydrogen' of a certain density, but any combination of elements which possesses a definite function, either in the world or in the human organism, is also a 'hydrogen.'

"This kind of definition of matters enables us to classify them in the order of their relation to life and to the functions of our organism.

"Let us begin with 'hydrogen' 768. This 'hydrogen' is defined as food, in other words, 'hydrogen' 768 includes all substances which can serve as 'food' for man. Substances which cannot serve as 'food,' such as a piece of wood, refer to 'hydrogen' 1536; a piece of iron to 'hydrogen' 3072. On the other hand, a 'thin' matter, with poor nutritive properties, will be nearer to 'hydrogen' 384.

" 'Hydrogen' 384 will be defined as water.

" 'Hydrogen' 192 is the air of our atmosphere which we breathe.

"'Hydrogen' 96 is represented by rarefied gases which man cannot breathe, but which play a very important part in his life; and further, this is the matter of animal magnetism, of emanations from the human body, of 'n-rays,' hormones, vitamins, and so on; in other words, with 'hydrogen' 96 ends what is called matter or what is regarded as matter by our physics and chemistry. 'Hydrogen' 96 also includes matters that are almost imperceptible to our chemistry or perceptible only by their traces or results, often merely presumed by some and denied by others.

" 'Hydrogens' 48, 24, 12, and 6 are matters unknown to physics and chemistry, matters of our psychic and spiritual life on different levels.

"Altogether in examining the 'table of hydrogens,' it must always be remembered that each 'hydrogen' of this table includes an enormous number of different substances connected together by one and the same function in our organism and representing a definite 'cosmic group.'

"'Hydrogen' 12 corresponds to the 'hydrogen' of chemistry (atomic weight 1). 'Carbon,' 'nitrogen,' and 'oxygen' (of chemistry) have the atomic weights: 12, 14, and 16.

"In addition it is possible to point out in the table of atomic weights elements which correspond to certain hydrogens, that is, elements whose atomic weights stand almost in the correct octave ratio to one another. Thus 'hydrogen' 24 corresponds to fluorine, Fl., atomic weight 19; 'hydrogen' 48 corresponds to Chlorine, Cl., atomic weight 35.5; 'hydrogen' 96 corresponds to Bromine, Br., atomic weight 80; and 'hydrogen' 192 corresponds to Iodine, I., atomic weight 127. The atomic weights of these elements stand almost in the ratio of an octave to one another, in other words, the atomic weight of one of them is almost twice as much as the atomic weight of another. The slight inexactitude, that is, the incomplete

176

octave relationship, is brought about by the fact that ordinary chemistry does not take into consideration all the properties of a substance, namely, it does not take into consideration 'cosmic properties.' The chemistry of which we speak here studies matter on a different basis from ordinary chemistry and takes into consideration not only the chemical and physical, but also the psychic and cosmic properties of matter.

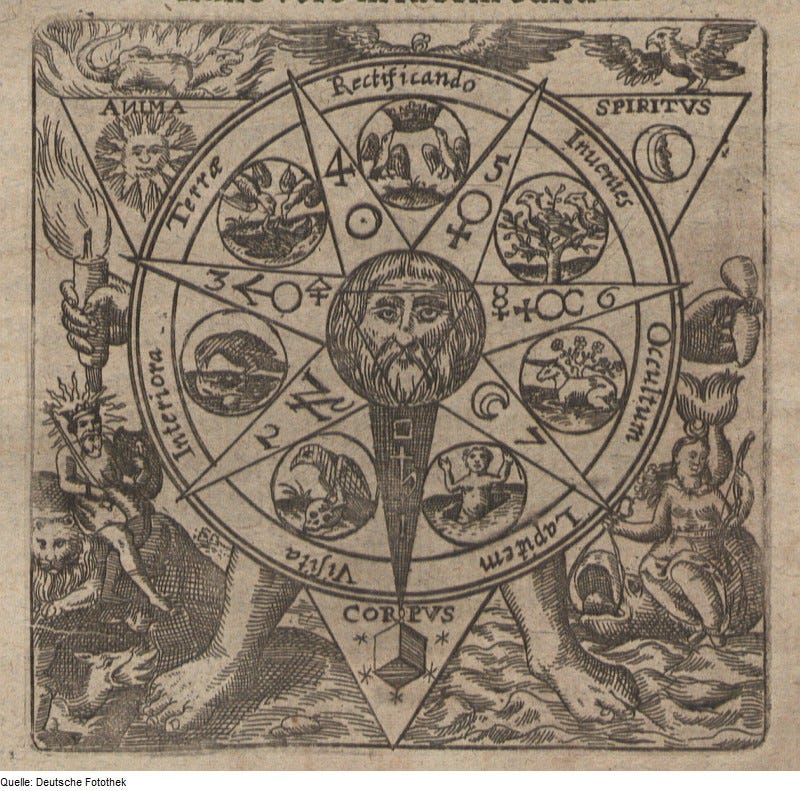

"This chemistry or alchemy regards matter first of all from the point of view of its functions which determine its place in the universe and its relations to other matters and then from the point of view of its relation to man and to man's functions. By an atom of a substance is meant a certain small quantity of the given substance that retains all its chemical, cosmic, and psychic properties, because, in addition to its cosmic properties, every substance also possesses psychic properties, that is, a certain degree of intelligence. The concept 'atom' may therefore refer not only to elements, but also to all compound matters possessing definite functions in the universe or in the life of man. There can be an atom of water, an atom of air (that is, atmospheric air suitable for man's breathing), an atom of bread, an atom of meat, and so on. An atom of water will in this case be one-tenth of one-tenth of a cubic millimeter of water taken at a certain temperature by a special thermometer. This will be a tiny drop of water which under certain conditions can be seen with the naked eye.

"This atom is the smallest quantity of water that retains all the properties of water. On further division some of these properties disappear, that is to say, it will not be water but something approaching the gaseous state of water, steam, which does not differ chemically in any way from water in a liquid state but possesses different functions and therefore different cosmic and psychic properties.

"The 'table of hydrogens' makes it possible to examine all substances making up man's organism from the point of view of their relation to different planes of the universe. And as every function of man is a result of the action of definite substances, and as each substance is connected with a definite plane in the universe, this fact enables us to establish the relation between man's functions and the planes of the universe."

I ought to say at this point that the "three octaves of radiations" and the "table of hydrogens" derived from them were a stumbling block to us for a long time. The fundamental and the most essential principle of the transition of the triads and the structure of matter I understood only later, and I will speak of it in its proper place.

In my exposition of G.'s lectures in general, I am trying to observe a chronological order, although this is not always possible as some things were repeated very many times and entered, in one form or another, into almost all lectures.

177

Upon me personally the "table of hydrogens" produced a very strong impression which, later on, was to become still stronger. I felt in this "ladder reaching from earth to heaven" something very like the sensations of the world which came to me several years before during my strange experiments when I felt so strongly the connectedness, the wholeness, and the "mathematicalness" of everything in the world.1 This lecture, with different variations, was repeated many times, that is, either in connection with the explanation of the "ray of creation" or in connection with the explanation of the law of octaves. But in spite of the strange sensation it gave to me I was far from giving it its proper value the first times I heard it. And above all, I did not understand at once that these ideas are much more difficult to assimilate and are much deeper in their content than they appeared from their simple exposition.

I have preserved in my memory one episode. It happened at one of the repetitions of this lecture on the structure of matter in connection with the mechanics of the universe. The lecture was read by P., a young engineer belonging to G.'s Moscow pupils, whom I have mentioned.

I arrived when the lecture had already begun. Hearing familiar words I decided that I had already heard this lecture and therefore, sitting down in a corner of the large drawing room, I smoked and thought of something else. G. was there too.

"Why did you not listen to the lecture?" he asked me after it was over.

"But I have already heard it," I said. G. shook his head reproachfully. And quite honestly I did not understand what he expected from me, why I ought to listen for a second time to the same lecture.

I understood only much later, when lectures were over and when I tried to sum up mentally all I had heard. Often, in thinking a question over, I remembered quite distinctly that it had been spoken of at one of the lectures. But what precisely had been said I could unfortunately by no means always remember and I would have given a great deal to hear it once more.

Nearly two years later, in November, 1917, a small party of us consisting of six people, among whom was G., was living on the Black Sea shore twenty-five miles north of Tuapse, in a small country house more than a mile from the nearest habitation. One evening we sat and talked. It was already late and the weather was very bad, a northeast wind was blowing which brought now rain, now snow, in squalls.

I was thinking just of certain deductions from the 'table of hydrogens,' chiefly about one inconsistency in this diagram as compared with another of which we heard later. My question referred to hydrogens below the normal level. Later on I will explain exactly what it was I asked and what, long afterwards, G. answered.

178

This time he did not give me a direct answer.

"You ought to know that," he said, "it was spoken of in the lectures in St. Petersburg. You could not have listened. Do you remember a lecture that you did not want to hear, saying you knew it already? But what was said then is precisely what you ask about now." After a short silence he said: "Well, if you now heard that somebody was giving the same lecture at Tuapse, would you go there on foot?"

"I would," I said.

And indeed, though I felt very strongly how long, difficult, and cold the road could be, at the same time I knew that this would not stop me.

G. laughed.

"Would you really go?" he asked. "Think—twenty-five miles, darkness, snow, rain, wind."

"What is there to think about?" I said. "You know I have walked the whole way more than once, when there were no horses or when there was no room for me in the cart, and for no reward, simply because there was nothing else to be done. Of course I would go without a word if somebody were going to give a lecture on these things at Tuapse."

"Yes," said G., "if only people really reasoned in this way. But in reality they reason in exactly the opposite way. Without any particular necessity they would face any difficulties you like. But on a matter of importance that can really bring them something they will not move a finger. Such is human nature. Man never on any account wants to pay for anything; and above all he does not want to pay for what is most important for him. You now know that everything must be paid for and that it must be paid for in proportion to what is received. But usually a man thinks to the contrary. For trifles, for things that are perfectly useless to him, he will pay anything. But for something important, never. This must come to him of itself.

"And as to the lecture, what you ask was actually spoken of in St. Petersburg. If you had listened then, you would now understand that there is no contradiction whatever between the diagrams and that there cannot be any."

But to return to St. Petersburg.

In looking back now I cannot help being astonished at the speed with which G. transmitted to us the principal ideas of his system. Of course a great deal depended upon his manner of exposition, upon his astonishing capacity for bringing into prominence all principal and essential points and for not going into unnecessary details until the principal points had been understood.

After the 'hydrogens' G. at once went further. "We want to 'do,' but" (he began the next lecture) "in everything we do we are tied and limited by the amount of energy produced by our

179

organism. Every function, every state, every action, every thought, every emotion, requires a certain definite energy, a certain definite substance.

"We come to the conclusion that we must 'remember ourselves.' But we can 'remember ourselves' only if we have in us the energy for 'self-remembering.' We can study something, understand or feel something, only if we have the energy for understanding, feeling, or studying.

"What then is a man to do when he begins to realize that he has not enough energy to attain the aims he has set before himself?

"The answer to this is that every normal man has quite enough energy to begin work on himself. It is only necessary to learn how to save the greater part of the energy we possess for useful work instead of wasting it unproductively.

"Energy is spent chiefly on unnecessary and unpleasant emotions, on the expectation of unpleasant things, possible and impossible, on bad moods, on unnecessary haste, nervousness, irritability, imagination, daydreaming, and so on. Energy is wasted on the wrong work of centers; on unnecessary tension of the muscles out of all proportion to the work produced; on perpetual chatter which absorbs an enormous amount of energy; on the 'interest' continually taken in things happening around us or to other people and having in fact no interest whatever; on the constant waste of the force of 'attention'; and so on, and so on.

"In beginning to struggle with all these habitual sides of his life a man saves an enormous amount of energy, and with the help of this energy he can easily begin the work of self-study and self-perfection.

"Further on, however, the problem becomes more difficult. Having to a certain extent balanced his machine and ascertained for himself that it produces much more energy than he expected, a man nevertheless comes to the conclusion that this energy is not enough and that, if he wishes to continue his work, he must increase the amount of energy produced.

"The study of the working of the human organism shows this to be quite possible.

"The human organism represents a chemical factory planned for the possibility of a very large output. But in the ordinary conditions of life the output of this factory never reaches the full production possible to it, because only a small part of the machinery is used which produces only that quantity of material necessary to maintain its own existence. Factory work of this kind is obviously uneconomic in the highest degree. The factory actually produces nothing—all its machinery, all its elaborate equipment, actually serve no purpose at all, in that it maintains only with difficulty its own existence.

"The work of the factory consists in transforming one kind of matter into another, namely, the coarser matters, in the cosmic sense, into finer ones. The factory receives, as raw material from the outer world, a number of coarse 'hydrogens' and transforms them into finer hydrogens by

180

means of a whole series of complicated alchemical processes. But in the ordinary conditions of life the production by the human factory of the finer 'hydrogens,' in which, from the point of view of the possibility of higher states of consciousness and the work of higher centers, we are particularly interested, is insufficient and they are all wasted on the existence of the factory itself. If we could succeed in bringing the production up to its possible maximum we should then begin to save the fine 'hydrogens.' Then the whole of the body, all the tissues, all the cells, would become saturated with these fine 'hydrogens' which would gradually settle in them, crystallizing in a special way. This crystallization of the fine 'hydrogens' would gradually bring the whole organism onto a higher level, onto a higher plane of being.

"This, however, cannot happen in the ordinary conditions of life, because the 'factory' expends all that it produces.

A New Model of the Universe, ch. 8, “Experimental Mysticism.”