Part of:

Continuing from:

For full citations of abbreviated references, see Introduction and Bibliography

Before Thomas and Olga de Hartmann met Gurdjieff, in December 19161 and February 1917,2 respectively, their life could be said to have been full of sweet things. They were very happily married and moved in the upper strata of society. Thomas de Hartmann was a well-respected musician, and in 1907, in spite of being a Guards Officer, "in recognition of his talent, the Tsar authorized Thomas’s release from active service to the status of reserve officer so that he could devote his full time to music,"3 that music which was the centre of his life.4

They had their first quarrel when Thomas told Olga that he had met without telling her the man described in a typescript of Glimpses of Truth that he had given her to read, that is, Gurdjieff.5 It’s as if meeting Gurdjieff, from the very beginning, put a spanner in the works of their well-ordered and satisfactory lives from the ordinary point of view. But life had been satisfactory except for one thing: "‘Without inner growth,’ Thomas de Hartmann said to Gurdjieff during his first meeting, ‘there is no life at all for me; both my wife and I are searching for a way to develop.’ "6 Gurdjieff accepted them into his work, and then, from music being the centre of his life, Hartmann, together with his wife, were now among people "for whom the answering of inner questions, the finding of a way to real, active work on themselves, truly formed the centre of their lives."7 They were being introduced to a different kind of music.

As to their being happily married, at Olga's first meeting, she was quite disturbed when she heard Gurdjieff say that, "love is the strongest obstacle to man’s development." However, he then went on to put the question, "But what kind of love?" He spoke of real love being different, but that egoistic love hinders.8 The latter kind of "love" can be seen to be connected to hypnosis, to any identification, and especially to the mass psychosis of war.

Thomas, having been recalled to his regiment, would be on his way to the front by the end of February 1917.9 But Gurdjieff told him, "never let yourself be seized by the war psychosis. Remember yourself . . . Don’t forget to remember yourself," and that when the revolution broke out totally, it would no longer make any military sense to be at the front, and that he should "Try to get away and come where I shall be."10

So their lives change from outer “roses” of an externally happy life and the inner thorns of the knowledge of spiritual lack, of dissatisfaction with oneself, to a kind of reversal. Outer conditions became tough, and there was unusual struggle with inner and outer resistances, but there was the inward happiness of the conviction that now they were connected with someone who knew the way of self-transformation, and with others with whom they could work. The outer reversal might be seen to be represented by Gurdjieff’s instruction to Thomas de Hartmann that he must forego his usual two pieces of sugar in his tea.11 Gurdjieff, at the same time, simply on the external level, helped them escape the dangers of the revolution, and saved Thomas de Hartmann’s life when he became ill with typhoid. It seems impossible, however, that this outer good could have been achieved without the primary focus being on inner work, of struggle against self, on both sides.

It is interesting, and may be instructive, from a literal and also symbolic level, to look at Gurdjieff’s actions towards Thomas de Hartmann when he was ill, and Thomas and Olga’s own experiences during this period, some of which have already been mentioned in this series of posts.

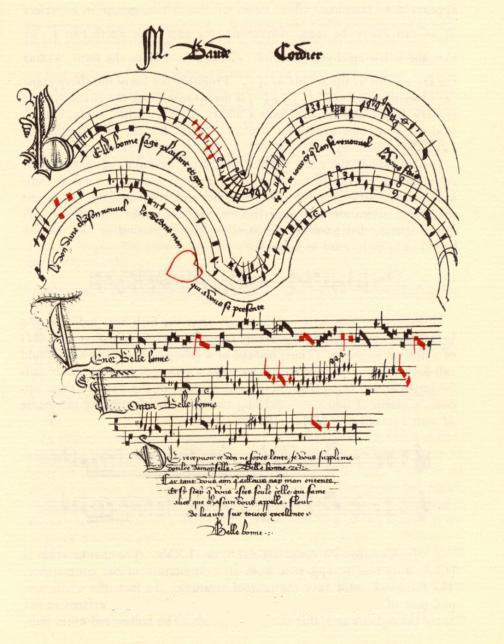

During his illness, Hartmann experienced delirium and manifested violence towards all those around him trying to help him, including overturning a table with burning candles and almost making Gurdjieff fall down.12 At one time, only their servant and companion, Marfousha, could help him with some “evil notes,” as it were, that were plaguing him. Hartmann describes the hallucination that "red musical notes were running through the room and would not leave me in peace." His wife tried to reassure him without avail that they were not really there. The “simple peasant girl,” however, knew exactly what to do, and gathered them up into her apron and threw them away, and he was relieved and slept.13 A shrewd psychological technique, one could say, entering the patient’s world, and taking part in its drama, no matter that its “reality” is utterly different from one’s own. However, vibrations and their transformations and interpenetrations up and down the scale are at the essence of Gurdjieff's teaching, and these musical notes that were so troubling to Hartmann needed to be expelled, or neutralised, in some way. There may also be something of an echo in this scenario of Hartmann's red musical notes with the “evil-carrying vibrations” played on the grand piano by Hadji Asvatz Troov in Gurdjieff’s first series.14 Perhaps one can see Marfousha as representing "good-carrying" vibrations,15 taking away the pain and disturbance of Hartmann, represented by the red musical notes.

Continues in: